The first hour or two of the 2010 edition of Les Vingt-Quatre Heures du Mans were a low point in Audi’s ultra successful Le Mans campaign of the past decade. They had largely dominated the period and now were being soundly beaten on sheer pace, by a quartet of Peugeot 908 HDi FAP coupés, the expensively revised R15+ just could not hack it. It was a general assumption that the factory cars were bullet proof in terms of reliability, so Audi would have to keep plugging away and hope for better days.

However the pace of the two factory diesel teams was extreme, pushing the cars to the limit………….and beyond. We were into uncharted territory, it was like a motorsport rerun of Ali-Fraser’s “Thrilla in Manila”, something was going to have to give.

Suddenly the screens were full of Pedro Lamy’s Peugeot limping around the track, front wheel askew, Bruno Vandestick, the irrepressible Le Mans commentator, whipping the crowd to attention. In fact the suspension had parted company with the monocoque, possibly this was the price to be paid for pole position, as this often occurs if cars are bouncing off the kerbs, whatever, the car was listed as a retirement. A small sliver of doubt crept into the French operation, a crack in their armour had appeared, what would be next?

In fact it was Audi that was next to flinch. Tom Kristensen in #7 tripped up over Andy Priaulx in the BMW Art Car. The M3 was crawling back to the pits, afflicted with one of the many punctures suffered up and down the field. By the time the Audi had been pulled from the gravel at Porsche Curves and the rear repaired, three laps had been lost and so had any reasonable chance of a win. Priaulx put his hands up, admitting that he had misjudged TK’s speed. He showed considerably more class than Audi boss, Dr Ulrich, who stormed down the pit lane to shout at BMW’s Charly Lamm. I can think of a few team principals down the years who would have not have endured a similar exhibition so calmly, imagine trying that crap with Tom Walkinshaw. It was a confirmation, if any were needed, of the enormous pressure that the Audi head honcho was under.

Darkness came and with it the Peugeot challenge gradually wilted, alternator failure and damage from a collision delaying two cars. Then came dawn and disaster at 7.02am as the engine of the #2 Peugeot exploded in flames, their race run. Audi was in front for the first time. This was amazing, Audi looked as if they just might pull off a major upset. The order came down from on high at Peugeot, go flat out and see if the Audis might be caught or break too.

The expression les merdes volent en escadrille best summed up the next few hours for the French as both of their challengers suffered engine failure while chasing the Audis. Olivier Quesnel maintained a terse “No Comment” when questioned about the root of the problem. In the paddock a whisper of piston broke took hold. It could explain as to how the cars were faster despite a 5% reduction in restrictor size over 2009. Whatever, Peugeot’s dream was now a nightmare.

In the final analysis Peugeot shot themselves in both feet, failing to take a victory that seemed at one stage to be theirs alone. Credit must be given to Audi for never giving up and building a car that ran without fault, true Le Mans virtues. #9 spent only 36 minutes in the pits during the race. Another goal that it scored and one that may never be surpassed, was the distance record. #9 completed 397 laps or 3,362 miles, an average speed of just over 140 miles per hour. The previous record had stood since 1971…………evidence of just how hard the fight had been.

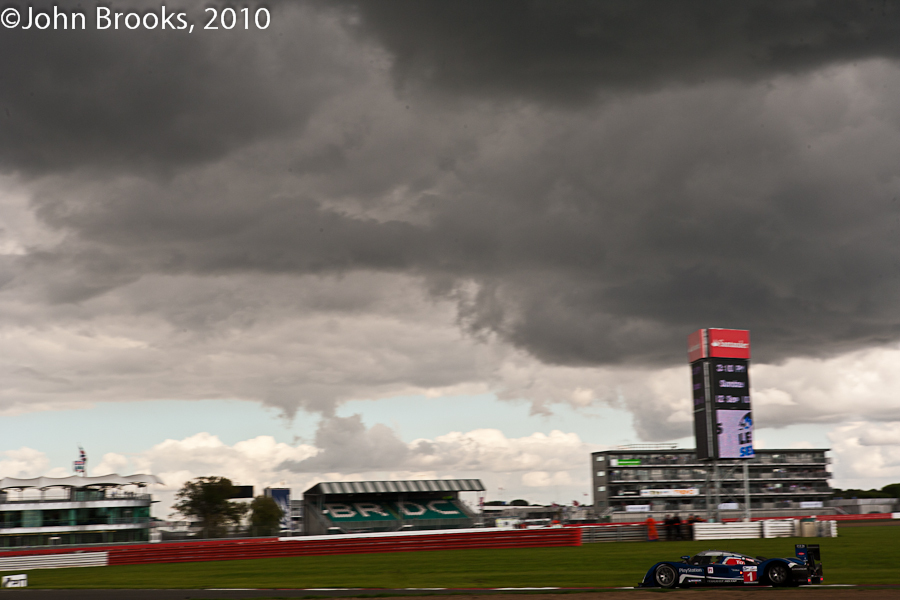

How does a team pick themselves from such a public and crushing disappointment? Well it is the mark of true champions to be able to do so and that is how you would describe Peugeot. At Le Mans there had been an announcement by the powers that be, there would be a new competition, the Intercontinental Le Mans Cup, catchy name, that would, it was hoped, evolve into a proper World Championship. Silverstone in September would see the inaugural event.

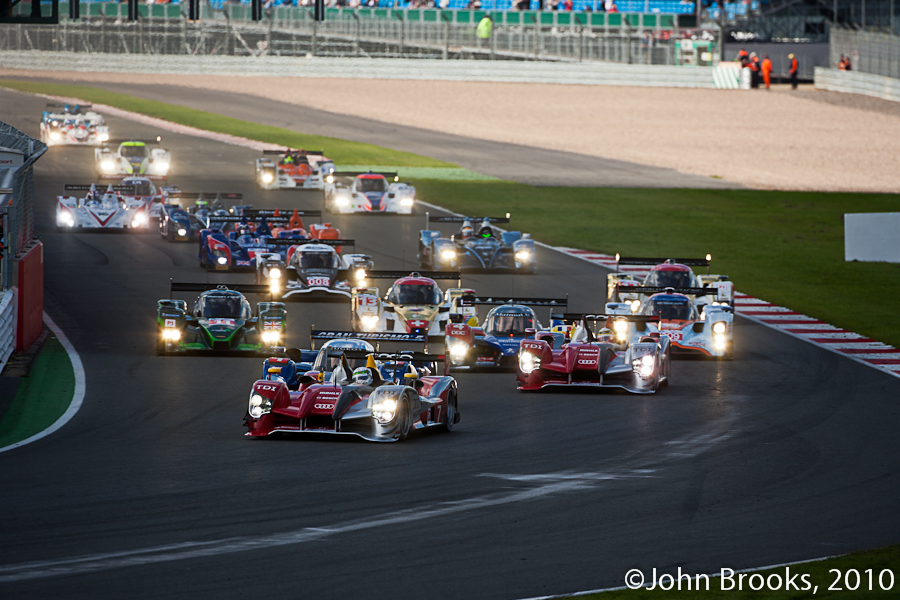

Audi fielded two R15+ prototypes against two 908s, one factory and one ORECA run. Pole went to Audi but there was a suspicion around the pressroom that the French still had the better car.

So it proved with the 2009 spec ORECA-run 908 backing up the factory entry for a Peugeot 1-2. Audi defeated once again away from La Sarthe and Peugeot back on track.

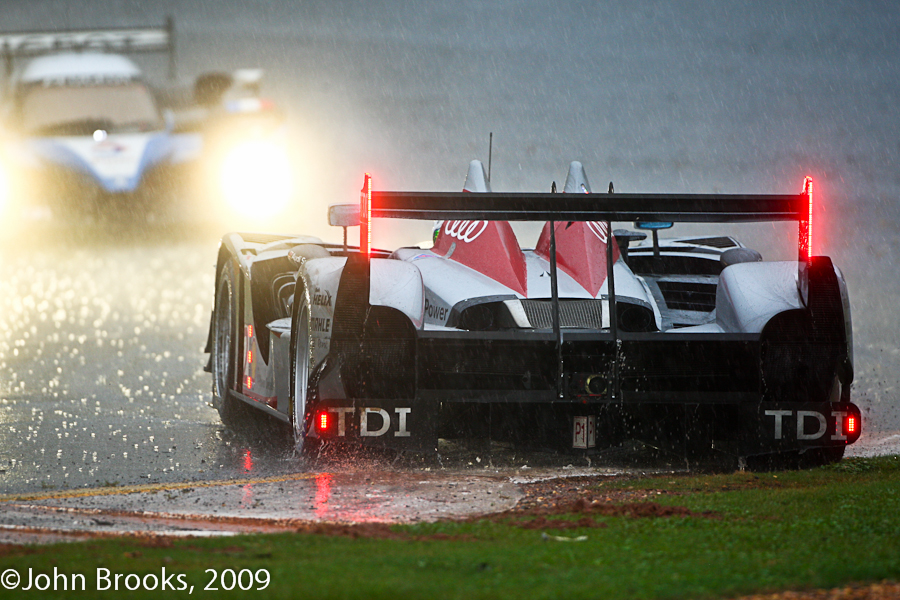

A few weeks later and we were across the Atlantic for the Petit Le Mans. The two factories seemed evenly matched around the sinuous Road Atlantic track, the outright speed of the 908 being matched by the commitment the Audi squads in the persistent traffic.

As the shadows lengthened there was a three-way fight at the top of the order, it was going to be a scrap all the way to the finish.

Except it wasn’t. Capello’s Audi slowed and pitted unexpectedly, leaving the 908s to romp away. As the PR Release put it

Dindo Capello, who was leading at that time, had to come in for an unscheduled pit stop because an insert in his helmet prescribed by the regulations had come loose and the fireproof balaclava started to cover his eyes. Without being able to see anything, Capello had to let the Peugeot behind him pass and head for the pits in a blind flight.

In his own words. “But then the nightmare started. At first I didn’t have a clue as to what was happening. I had the feeling that the helmet was suddenly three sizes larger than before. We later found out that the E-Ject insert in the helmet had come loose. I was even lucky not to have had an accident since I was completely blind in one turn because the helmet slipped across my eyes. Even after so many years you can still experience something new.”

Another race to Peugeot, though the sympathy was with Audi.

The final encounter of the diesels for 2010 was to be in Zhuhai, the ILMC title was at stake as was Audi’s pride.

Once again there was little to choose between the factories and in the end it all came down to the last few laps and some questionable driving by a lapped Bourdais who impeded Kristensen’s pursuit of Sarrazin. Predictably there no action from the officials and a bit of light hand-bagging after the race but another win had slipped away.

For Audi 2010 had been a difficult year to say the least. Victory at Le Mans was the one shining light, they had been hammered in the DTM and the R8 GT3 project had failed to get the desired results. Something must be done.

Peugeot had recovered strongly from the nightmare in June and had serious plans to gain revenge for that humiliation. 2011 was going to another cracker.

John Brooks, November 2011