Malcolm Cracknell was one of the pioneers of endurance racing coverage on the then new-fangled internet. What set him apart from the throng of wanabees and fans with passes who invaded Media Centres at that time was the fact that he actually had a clue. Crackers understood both racing and people, especially the gang of scoundrels who chose endurance sportscars as their platform. Even after years of enforced retirement he observes the distant paddocks with more acuity than many who actually attend the races. Time spent chewing the fat with him over the phone is never wasted and is generally punctuated by laughter and seasoned with salacious gossip, ancient and modern.

When this SRO book was published last year I asked him to write a review from his own perspective, he was witness to much of the narrative. He did so promptly, which is more than can be said for my performance in posting the piece. So with humble apologies from the Editor for the delay here is the weekend treat.

25 YEARS OF GT RACING

STEPHANE RATEL AND SRO MOTORSPORTS

This is an extraordinary book, in so many ways.In terms of value for money, it has to be a bargain: £75 for a glossy, 406 page volume, packed with superb photographs, suggests to me that it has to be subsidised to some degree.

I’ll add a ‘but’ here though: this needs to be described as a hagiography (a biography that treats its subject with undue reverence). Stéphane Ratel is largely portrayed as a God-like figure, his SRO the salvation of GT racing – which is certainly true in many ways.

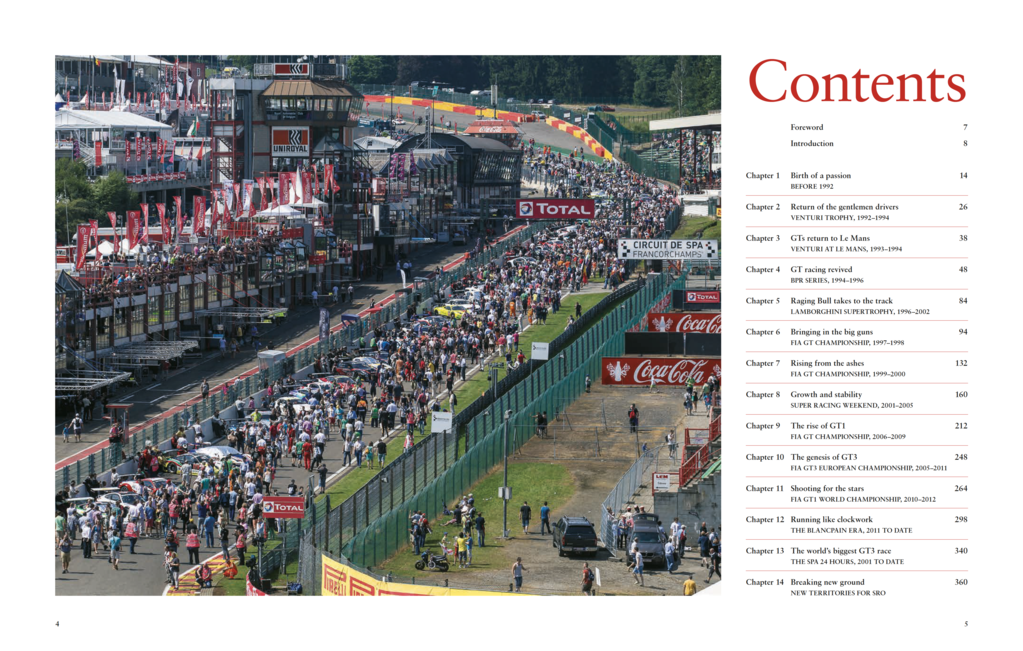

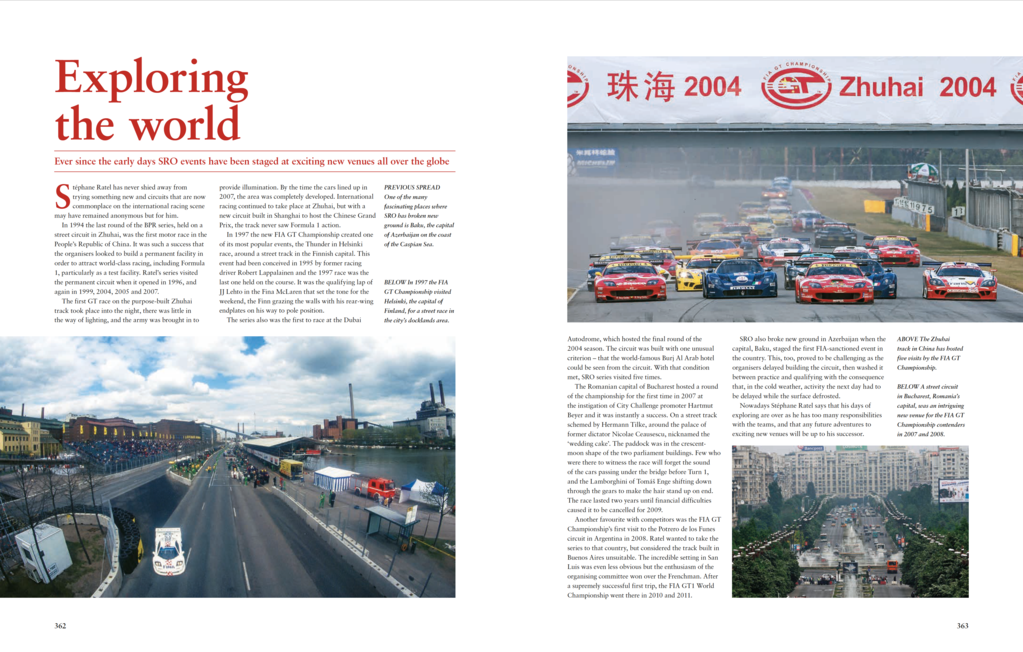

Andrew Cotton tells more than the story of 25 years of GT racing: he begins with Ratel’s tragic childhood and describes the young man’s ‘playboy years’, importing supercars from California to re-sell in Europe at a healthy profit, then organising a ‘Cannonball Run’ in France (Paris to San Tropez) for his wealthy mates, which developed into the Venturi Trophy (1992-4, which saved the company) – and finally, with Jürgen Barth and Patrick Peter, he created the BPR Series.

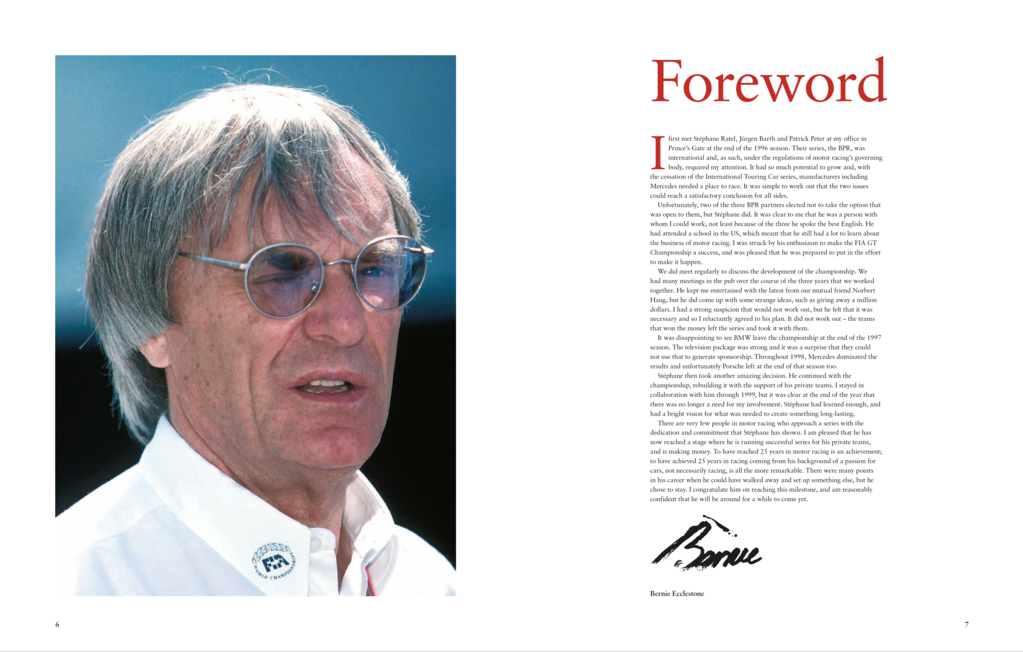

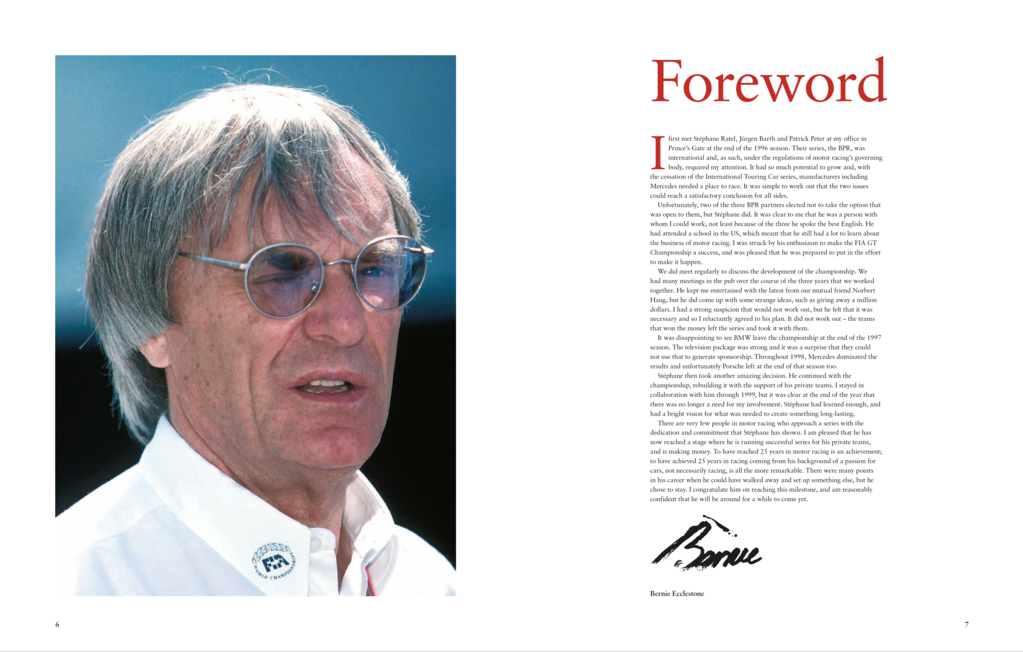

Was that the high point of GT racing in the modern era? In many ways it probably was – at least in terms of the way it captured the imagination of the public. But as we know so well, Porsche and then Mercedes initiated a very rapid boom and bust – and Andrew Cotton reveals one (of many) fascinating tales that perhaps had more of an impact on Ratel the businessman than any other. I won’t spoil it for those of you considering buying the book, but the man who wrote the foreword, one B. C. Ecclestone, was involved – and taught Ratel a very important lesson.

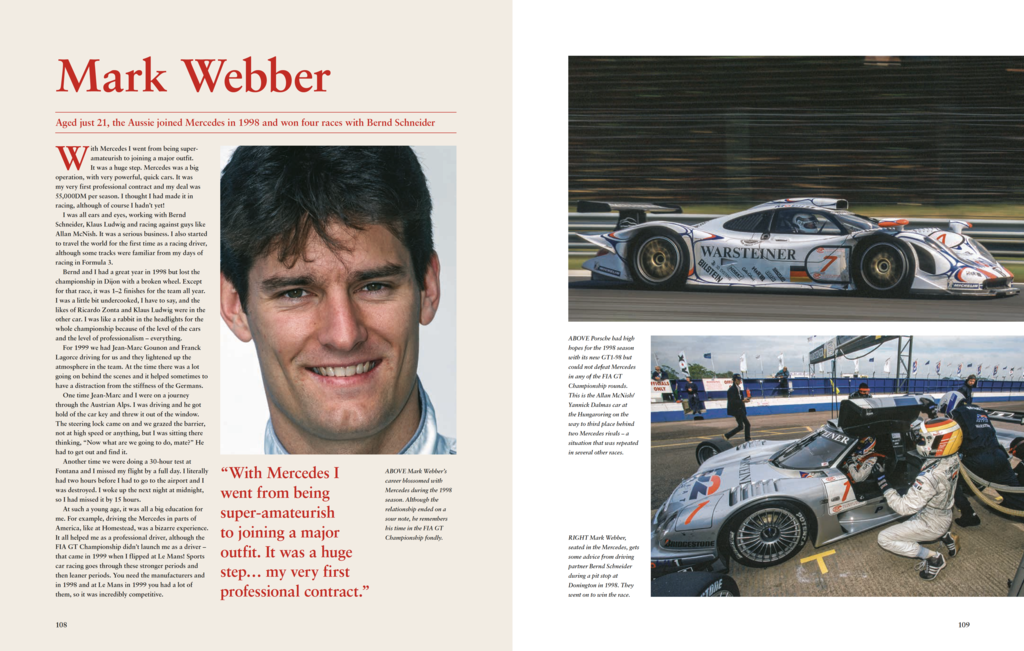

When the FIA GT Championship ‘expired’ at the end of a disappointing 1998 season, only one man was prepared to try and salvage the thing, and the last 19 years have seen Stéphane Ratel and SRO carry it on with varying degrees of success.

1999 was probably the low point, but if you’re determined enough, you can follow all the ups and downs to the present day. It’s a convoluted tale, but to his credit, Ratel has stuck at it and is to be admired for that.

It’s been a battleground along the way, with GT2s becoming GT1s, three hour races becoming two, N-GTs briefly becoming the headline class – and then (I think this is missing from the book), in August 2007, there was an extraordinary Ratel proposal for the future of GT racing which was so convoluted that I’d need a 1,000 words to explain it.

That didn’t happen, but Ratel does admit that his plan for a GT1 Championship, of one hour races, was a mistake. Ironically, he’d already discovered what the future should be with his GT3 idea. Who, among those present at the launch of the FIA GT3 Championship, at a wet Silverstone in April 2006, could have guessed where this was going?

I was astonished to read that over 1,500 GT3 racers have been constructed in the last ten or so years. Bentley has recently announced that it will ‘only’ build 40 of its latest GT3 racer, compared to the 100 to 200 cars that Audi and Mercedes have built. Extraordinary figures, all of them.

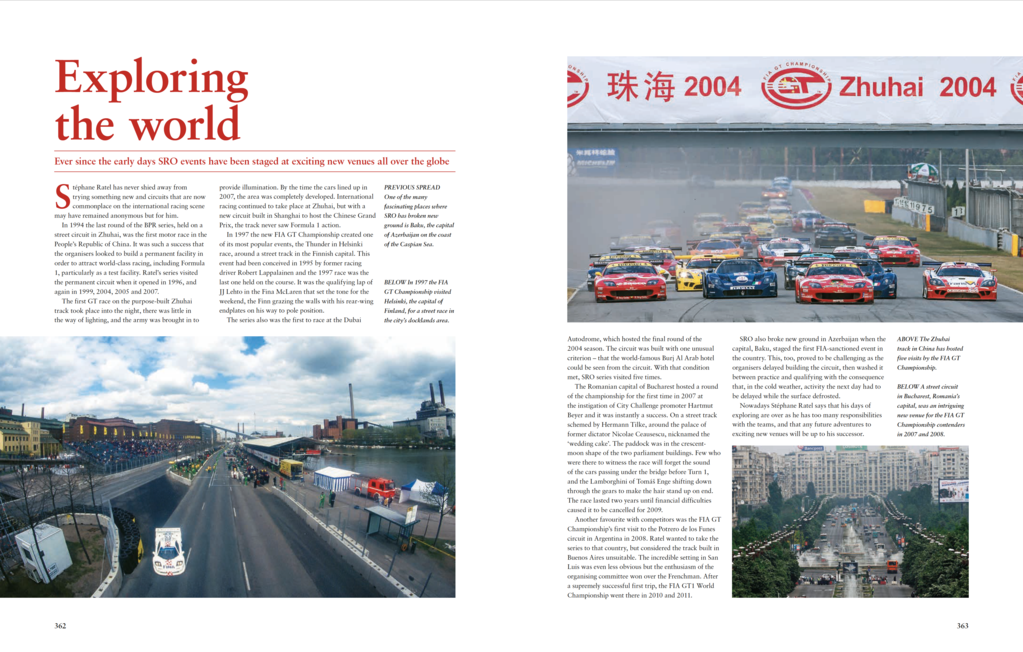

‘Ratel series’ have expanded across the globe to soak up the demand, and it was intriguing to rediscover how the FIA tag came to be dropped, in favour of a slightly less formal, but more commercial, Blancpain name.

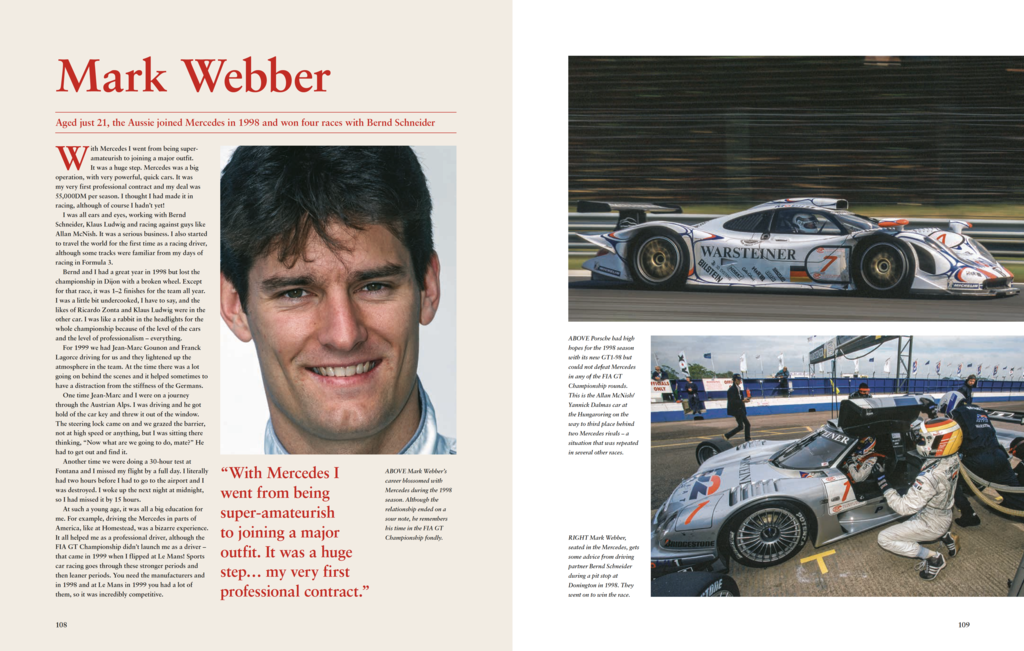

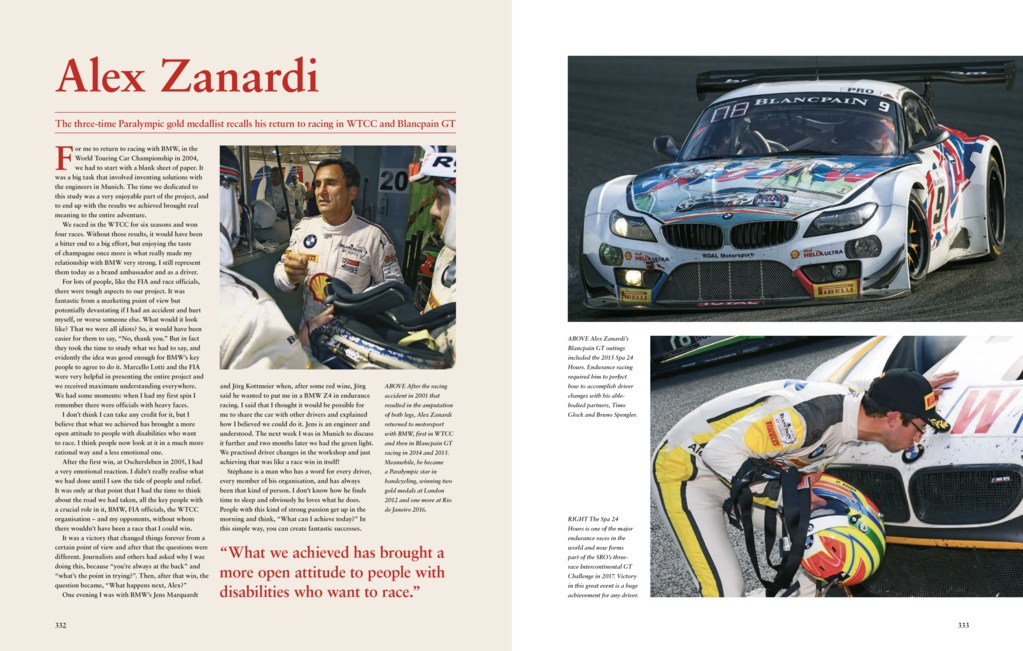

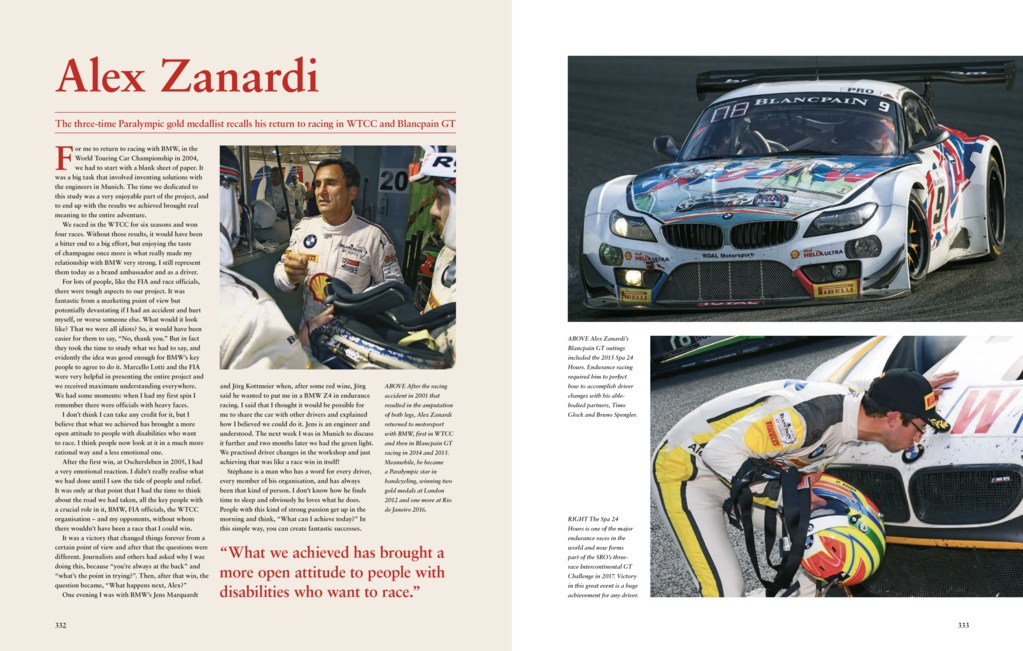

The book is punctuated with interviews / mini-biographies of a huge number of (not always) well known names who have been involved in SRO GT events during the last 25 years – many of whom have fascinating stories to tell.

In conclusion, I would suggest that there are only two things missing from this book. One would be a results section – but in fairness, there have been so many races, it would need another book to encompass their results.

The other would be any mention of any relationship between SRO and fans of GT racing – but fans don’t seem (with the exception of the Spa 24 Hours) to fit the SRO business model. Stéphane Ratel provides the cars, it’s up to the circuits to market their events to potential spectators. But with or without them, GT3 racing just seems to grow and grow.

Malcolm Cracknell, March 2018