As with most things that the last lot in power (the Blair/Brown Cabal) here in the UK touched, the Millennium Celebrations got screwed up. The Dome became a byword for the kind of badly executed, wildly over budget, grandiose gesture projects that were supposed to keep us all dazzled. Fiddling while Rome burned, they even got the date wrong, as us Gregorians reckon that the new era starts in 2001 not 2000. Whatever.

As with most things that the last lot in power (the Blair/Brown Cabal) here in the UK touched, the Millennium Celebrations got screwed up. The Dome became a byword for the kind of badly executed, wildly over budget, grandiose gesture projects that were supposed to keep us all dazzled. Fiddling while Rome burned, they even got the date wrong, as us Gregorians reckon that the new era starts in 2001 not 2000. Whatever.

In many ways the first major motor sport event of this Millennium, the 2001 Rolex 24 Hours, marked a more significant point than the 2000 edition held the previous January. Sure that had kicked off the Grand-Am set of races, and with a bang, but as those of us who have been around the tracks a while will tell you, organisations and their acronyms come and go. Yes, there had been a major battle between the factory teams of Viper and Corvette, eclipsing the supposedly faster prototypes, even the debuting Cadillac, but if Grand-Am represented anything it was not factory based competition.

As if to emphasise this point, by the start of 2001 both Dodge and Cadillac were gone, leaving Corvette’s team, Pratt & Miller, to try and beat the faster hoards of prototypes.

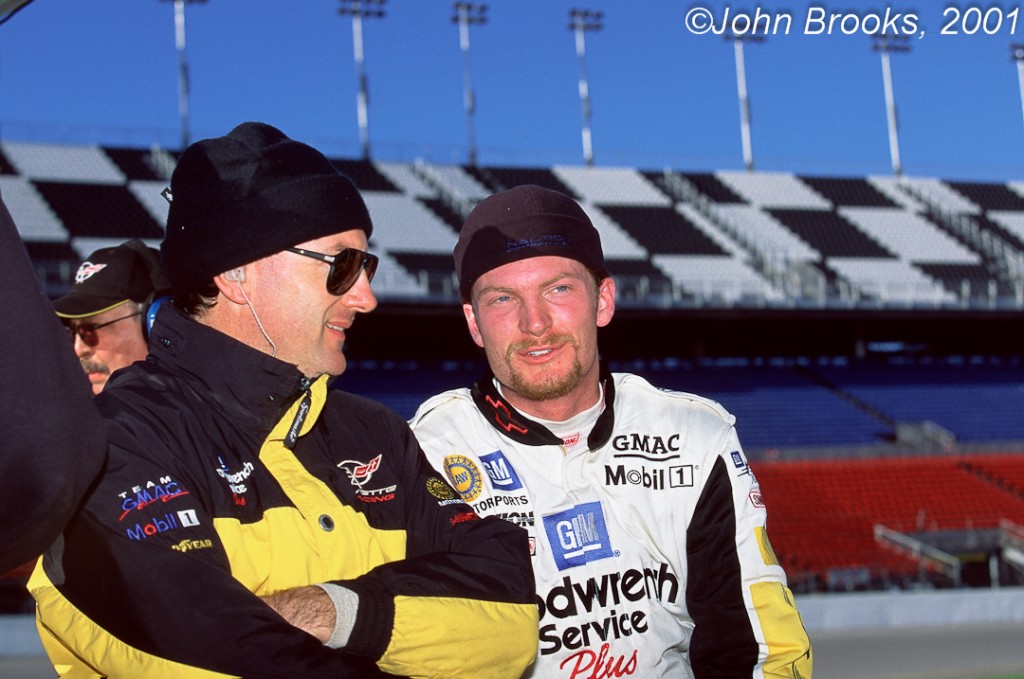

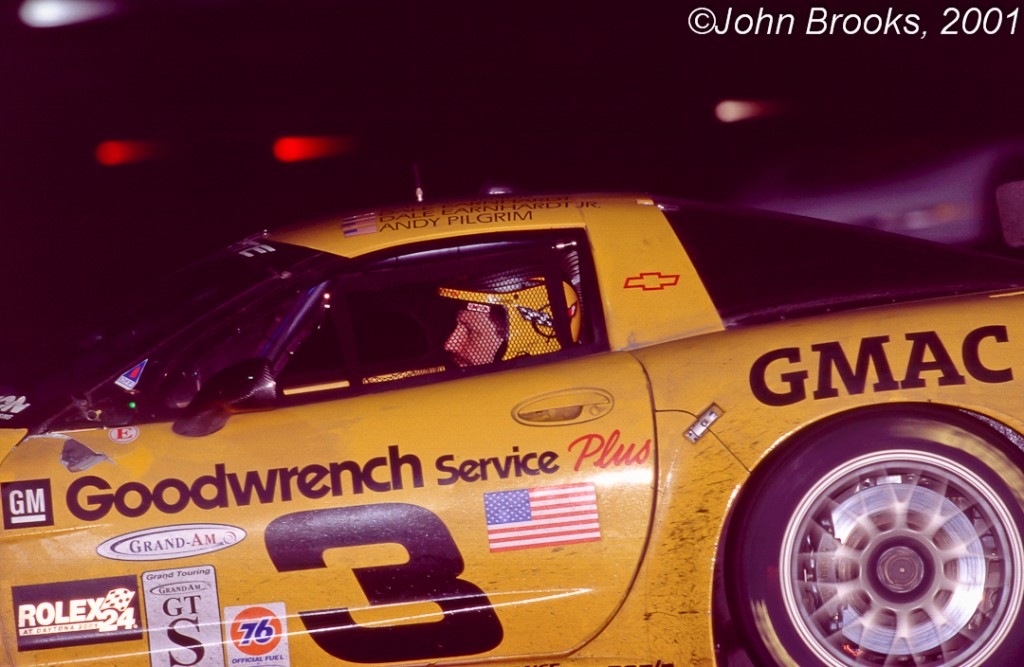

The big news from the Corvette camp was that NASCAR superstar, Dale Earnhardt Snr. was joining the line up in the #3 car (what else?). And that his son, Dale Jnr. would be with him plus regulars, Andy Pilgrim and Kelly Collins. The #2 Vette would be the insiders’ favourite though, whatever the fans thought, the combination of Ron Fellows, Johnny O’Connell, Franck Freon and Chris Kneifel would be amongst the best in the field.

Despite the lack of experience in driving endurance cars (or in the rain or at night) Earnhardt applied himself to the task in hand, really impressing his fellow drivers and the whole team.

That should have surprised no one, sportsmen do not reach the Olympian heights that Senior had over many years in NASCAR, without being both bright and hard working.

The process of adjustment to the new scene was greatly helped by the advice and friendship shown to the stars by Andy Pilgrim and Chris Kneifel, who talked through the areas of concern like the completely alien braking processes, the driving at night, the running in the rain. In return Earnhardt was able to bring his intimate knowledge of the Daytona banking to assist his team to be even quicker along the famous pavement.

Another big change from the NASCAR environment was that of being part of a squad of drivers but the Father and Son combo adjusted well to this aspect. I was on the fringe of the team due to friendly GM PR guy who kept me appraised of any happenings. He even introduced me to Dale, who considering our relative status, was extremely gracious, not a reaction I always encounter from some in the game.

The attention of the media was focused on #3, this was, after all, the heartland of NASCAR and Senior was their transcendent Super Star. This left the crew of #2 to get on quietly with preparations for the battle with the prototypes in the search for overall victory. There were stories at the time of Senior’s ambitions to race with Corvette in the following years, especially at Le Mans, he was a serious racer. I wrote about this later HERE

Perhaps the Ferrari 333 SP of Risi Competizione was the most popular choice for the top step of the podium at the race’s end. A hotshot team running the car, a driver line up that consisted of Ralf Kelleners, David Brabham, Eric van de Poele and Allan McNish plus the beautiful, sonorous Ferrari seemed to be the obvious selection. McNish has had his eye on a Rolex since winning his class in 1998 at Daytona, the year before the watches were awarded to all class winners not just the overall victors. Of course we are all too gentlemanly to ever mention this small omission in his career, maybe this would be his best chance to get hold of one the fabled timepieces without parting with actual cash. Fastest lap in practice of 1:41.118, if not in Qualifying, seemed to support the argument.

Another notable contender was the Porsche powered Champion Racing Lola B2K/10. Bob Wollek, Hurley Haywood, Dorsey Schroeder and Sascha Maassen would bring experience and speed to job in hand. The standard of the Champion Racing outfit was top line and with some assistance from Weissach this was more than a dark horse.

There were two Dyson Racing Riley & Scott Mklll Fords, that were always contenders for victory when they entered a race. They had won the Floridian classic in ’97 and ’99 and were looking for a hat trick.

Any team that could count on the talents of James Weaver, especially if joined by Andy Wallace and Butch Leitzinger, was going to be there or thereabouts. No Question.

So the question would be could the faster prototypes run reliably enough to beat the Corvette pair? Or would there be a repeat of the 2000 race that fell into the hands of the GT1 machines after the prototypes imploded?

Weaver got the jump on Jon Field’s Intersport Lola at the start and as the competitors made their way into the infield all hell broke loose. Norman Simon in the Bob Akin Motorsports Riley & Scott pirouetted, he reckoned he was tapped into the spin, others felt that too much aggression on cold tyres a more likely explanation.

Ron Fellows nearly ran his Corvette into Broward County trying avoid any possibility of contact, it was no way to start a 24 Hour race.

The race settled down after the indiscretions of the first lap, Weaver lead from Kelleners and Field and others in SportsRacing Prototype class all took spells in front during the opening stint.

Grand-Am was itself about to embrace a period of change, trying to find a formula that would give their competitors stability of rules and some form of cost capping to try and rein in budgets and keep the ALMS, ACO and FIA at bay. In 1999 the Grand-Am President, Roger Edmondson, had formed an alliance with John Mangoletsi and the European based Sports Racing World Cup with a plan for to run two races in 2000 at US venues with a combined grid of prototypes. Problem was that most of Mango’s Barmy Army, as we were almost affectionately known, did not want, nor could afford, to race on two continents. So only a handful of SRWC entries made the trip to Daytona and Road America that summer, so the concept was quietly dropped.

Grand-Am did not want to allow in the likes of Audi and similar factory teams to race in their series, they would destroy the opposition and lead to a dependence on their revenue streams, just ask the ALMS how that one worked out. However the technology that they and other manufacturers had introduced to prototype and GT competition could not be unlearned. The likes of Lola and Riley & Scott were forced by the demands of customers who wanted to race at Le Mans to follow in the escalation of technology and, of course, budget. It is around this time that the concept of the Daytona Prototypes began to appear in the thinking of the Grand-Am top brass as the answer to the conundrum. The final designs were still some time away but it was clear that Grand-Am and its showcase 24 hour race would operate to different rules and specifications to the rest of endurance racing. With the financial muscle of NASCAR and its allies behind the project, in particular Sun Trust Bank, it was possible to march to a different drum.

Dale Earnhardt Snr. was not the only star to be seen at Daytona that year. Paul Newman or simply PLN when racing, was an enthusiastic part of the Gunnar Racing Porsche team.

Unfortunately the 911 GT1’s performance did not match its looks and the elegant GT was an early retirement.

Another competitor getting an early bath was the Saleen S7-R of Paul Gentilozzi, a suspension failure led to retirement. The GTS category was thinning out.

Part two of this Retrospective tomorrow.

John Brooks, January 2011