Malcolm Cracknell was one of the pioneers of sports-car racing media on the internet as the World-Wide-Web was known in those innocent times. SportsCarWorld,TotalMotorSport and finally DailySportsCar were the introduction for most of us to the concept of paperless information in real time rather than on a weekly cycle. I joined Crackers on this journey at the start and now as we head for the winding down laps we spend time looking back as well as forward.

1999 is the target this time round for the Tardis……….

John Brooks and I are quite proficient at nattering away on the telephone. We call it “living in the past”, because we always return to discussing racing in a previous era.

For various reasons, I’ve been thinking about 1999 recently. Conveniently that’s two decades ago, but with the state of my brain, I’ve inevitably forgotten things that I wish I could remember – so I’ve had to consult the reference books (and video highlights).

What I do remember is that in late ’98, I was planning a trip to the season-opening Rolex 24. Presumably, finances dictated that it was either the Rolex or the Sebring 12 Hours (in early ’99). I have no idea why I chose the first of the two endurance classics): perhaps it was simply a desperate desire to escape the British winter for a few days? I’m guessing that I hadn’t absorbed how the maiden Petit Le Mans in ‘98 was going to set the tone for US endurance racing in years to come. Had I had any clue, I would have undoubtedly chosen Sebring.

But I certainly didn’t regret going to Florida in January. The first person I met after stumbling into the Speedway was Andy Wallace. Oddly, I’d not yet met Andy: our paths simply hadn’t crossed. But I was encouraged to find that he knew who I was and that he’d seen the last news item I’d posted, before dashing to Gatwick. That was an image of the new BMW prototype, which would make its debut at… Sebring. Andy and I were both a little perplexed by the BMW’s single, pointed roll hoop: the governing body was trying to mandate full width roll hoops, but BMW (and others, subsequently) had presumably found a way round the wording.

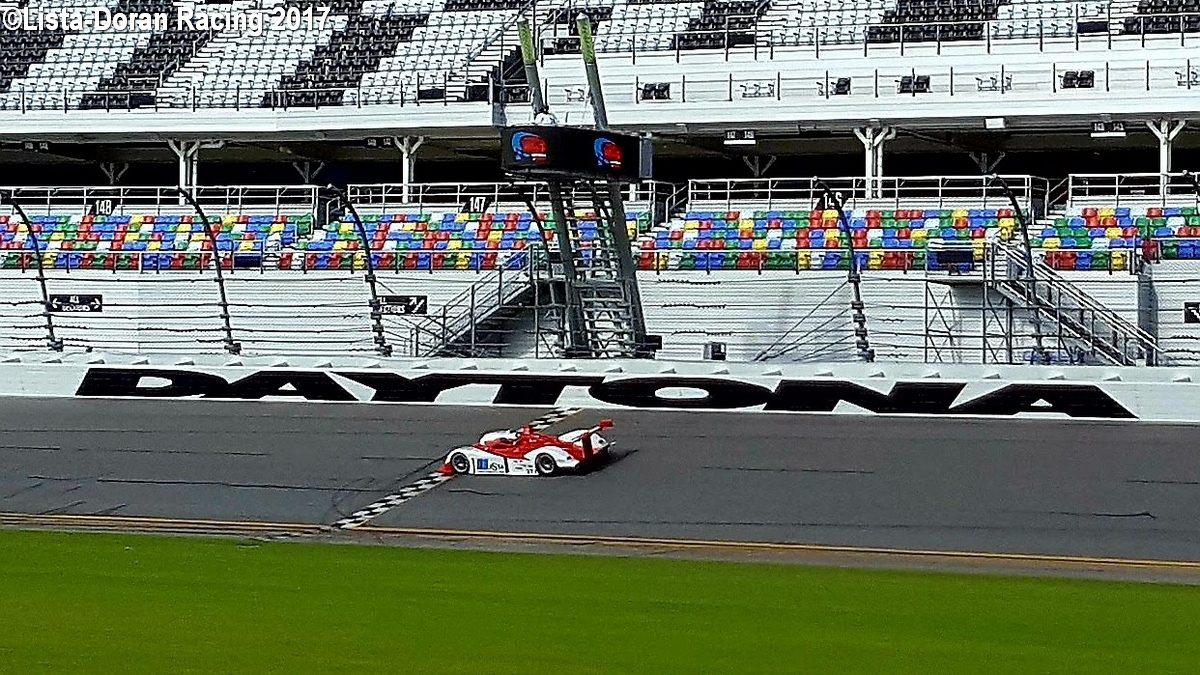

I loved Daytona! It was relatively straightforward to cover the race, live and single-handed, on the internet – by dashing to the nearby pit-lane every hour or two to grab a pitstop photograph and, hopefully, a comment from a competitor, then rushing back to the media center, to pick up the threads of the race.

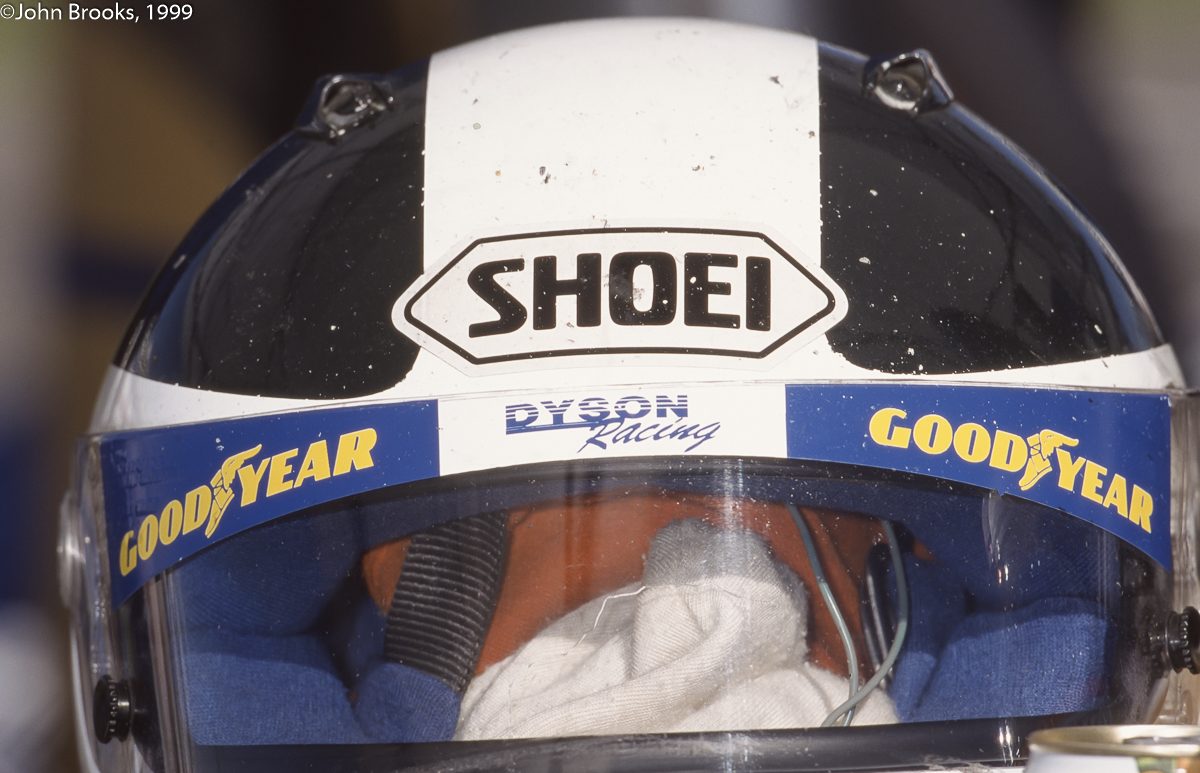

I was delighted when Dyson Racing took the overall win (AWOL, Butch Leitzinger and, appropriately, the way the season would evolve, EF-R) – and also with Brit David Warnock being part of the winning GTS crew in Roock’s Porsche. This was the event that saw the debut of the Corvettes, and thanks to a fortuitous bit of timing, I managed to grab 15 minutes with Doug Fehan, before the track opened. He talked me through the technical aspects of the car – and immediately planted a soft spot for the Corvettes in my brain. They weren’t race winners yet, and anyway, I always liked to see privateers beat the factory cars, which is just what the Roock Porsche managed.

Years later, James Weaver told me what he thought of the power output of the (restricted) Ford V8s in the Dyson R&Ss. ‘You can come past the pits (at Daytona) flat out, take your seat belts off, stand up, turn through 360 degrees, sit down, do your belts up – and still have time to brake for Turn 1’, was the essence of his complaint!

170mph+ was nowhere near fast enough for James. He wanted to reach at least 190. My only conversation with James during that Rolex meeting was a snatched “Stu Hayner has binned it (the #16) at the chicane,” at some point during the night.

Right, I’m getting near to the point of this piece now: the 1999 ALMS season, and the influence of one (great) man. I’m not about to review the whole ’99 season: I’m just going to refer to Sebring, the Road Atlanta sprint race and the finale at Las Vegas.

I think I’ve already told you that I finally ‘discovered’ youtube last year: I moved house, had to buy a new TV decoder thing, and really by accident, found that I could watch youtube on the TV (I can’t look at a laptop for any length of time, because of my illness). And there on youtube are highlights of all the ALMS races! Brilliant!

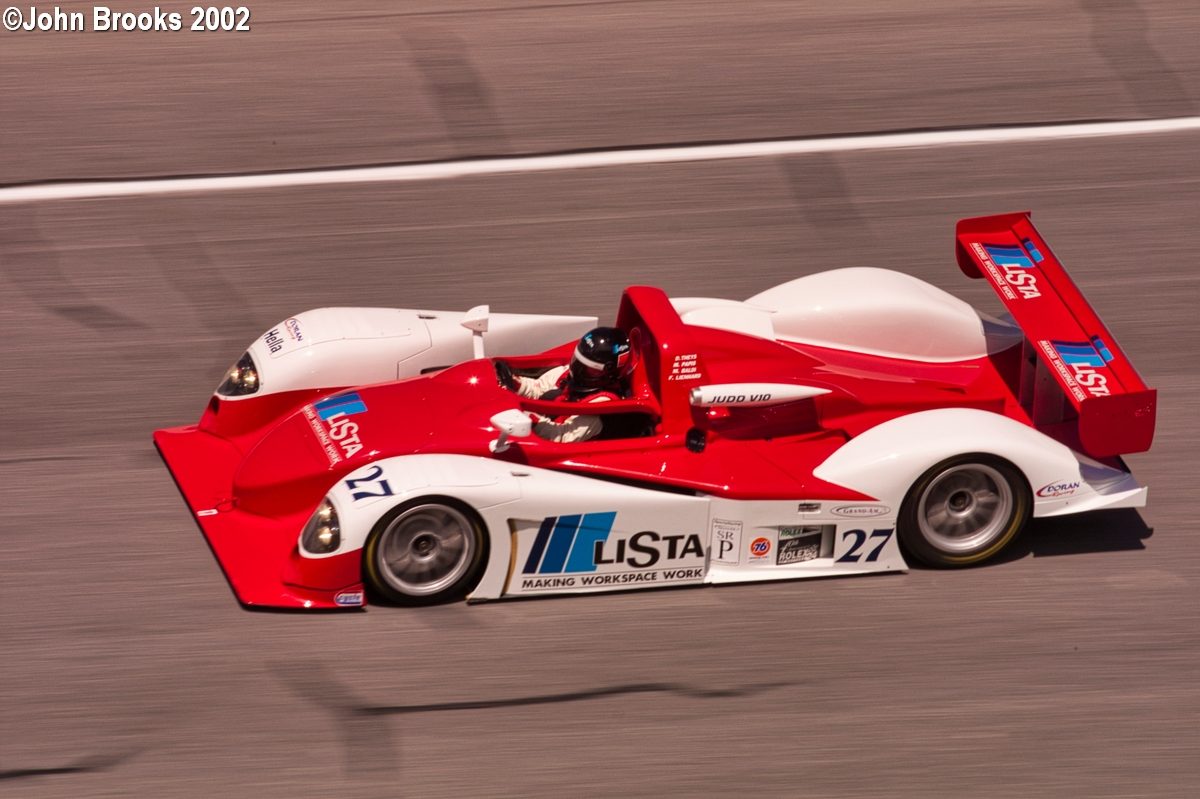

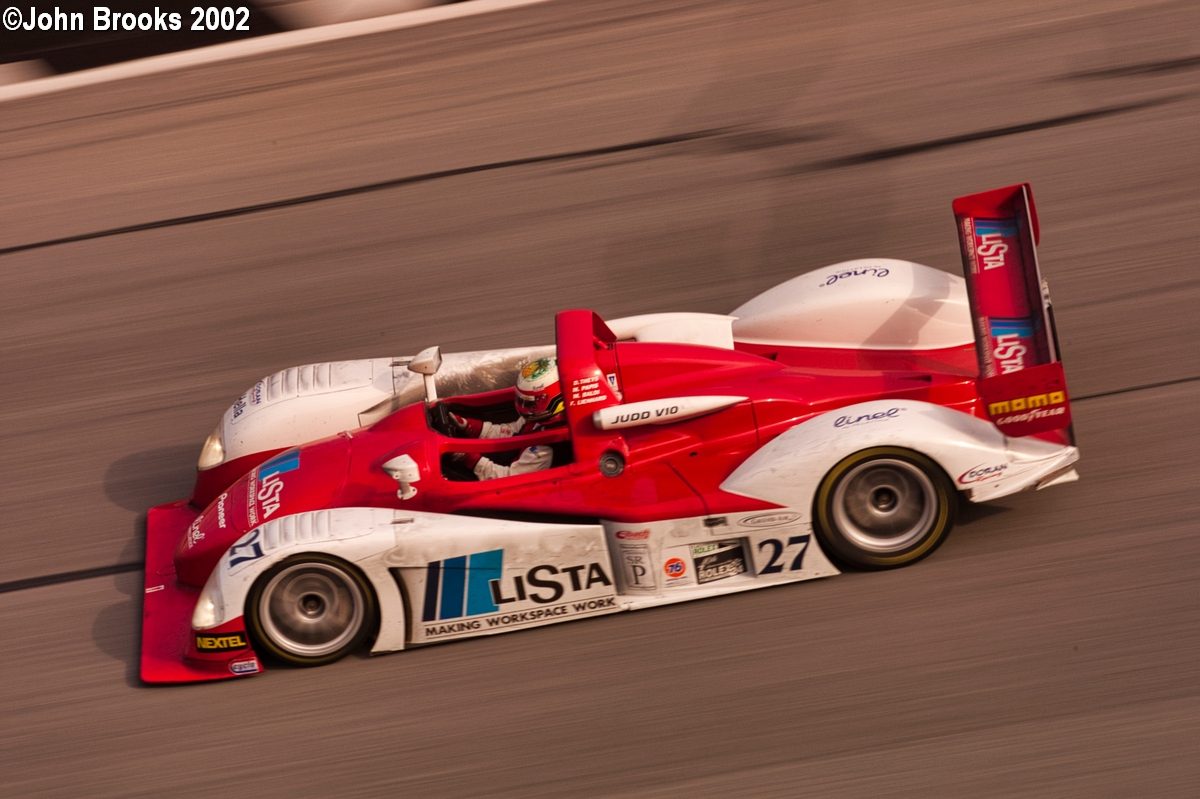

Sebring in ’99 was clearly an epic event, and I should have been there. A huge crowd, a fantastic entry (58 cars) – including van de Poele / Enge / Saelens in that gorgeous Rafanelli R&S Judd, a car that Eric vdP described somewhere (at the time) as, paraphrasing here, ‘the best car I ever drove’.

The admirable Belgian leapt into the lead at the start, and kept the BMWs at bay for 11 laps, before pitting with a misfire (it eventually retired after 185 laps). BMW tried to ‘shoot themselves in the foot’, which enabled the EF-R / Leitzinger Dyson R&S to stay in touch with the surviving factory entry of Lehto / Kristensen / Muller – which set up a great finale, with Weaver plonked in the R&S to try and chase down TK. He came up short by about 17 seconds at the flag. Great race!

Audi finished third and fifth with their original R8s – and a year later, the ultimate R8 would transform prototype racing. Porsches took the GTS and GT classes – as Corvette Racing continued to develop the C-5Rs.

I’ve no recollection of how (as it was then) sportscarworld.co.uk covered that Sebring race, but for the Road Atlanta event in April, the site had the benefit of Philip XXXX’s reporting skills. Alas, I can’t remember Philip’s surname, even though we have since been in touch on Facebook. How frustrating! Sorry Philip. But what a classic race you saw that day!

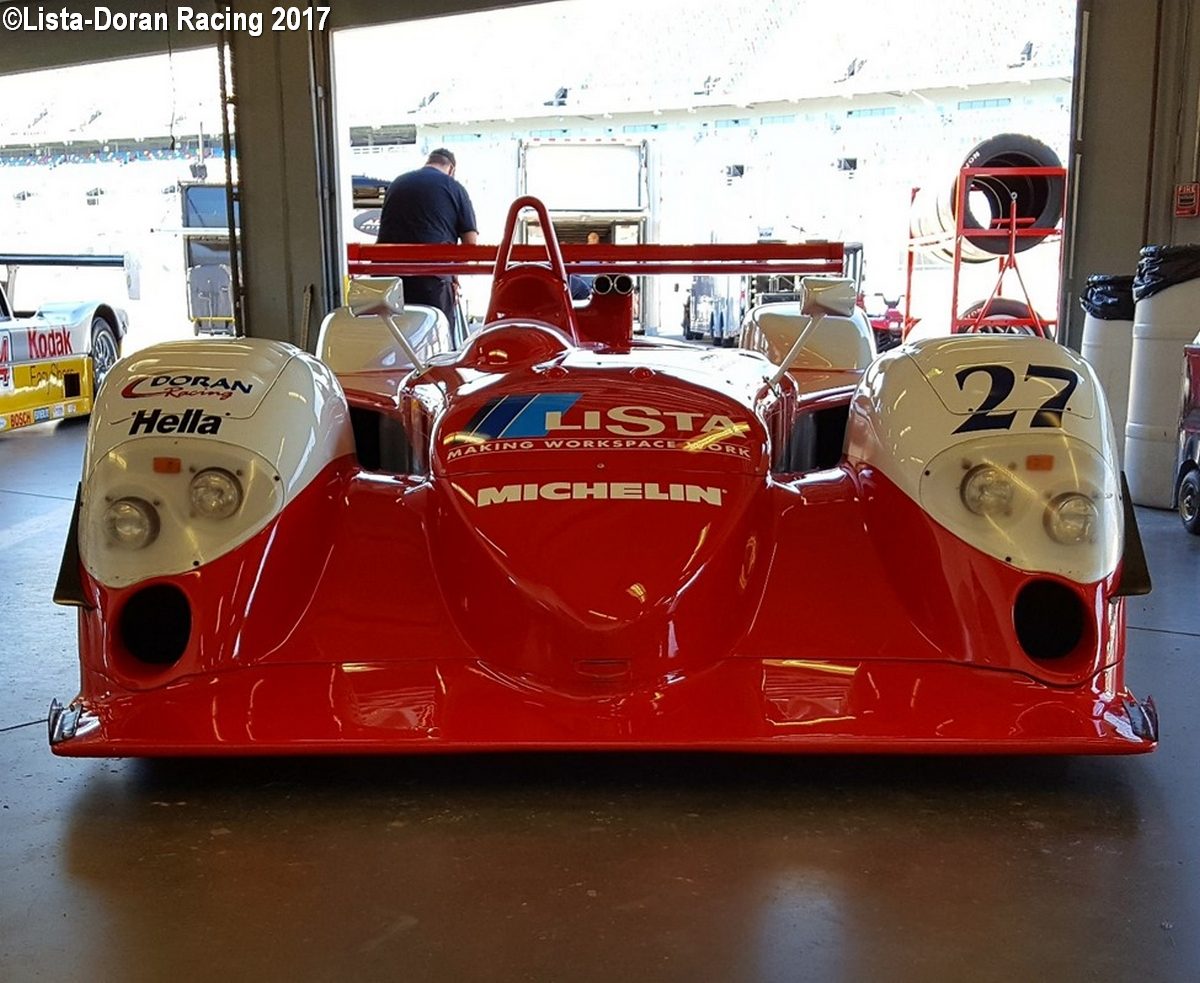

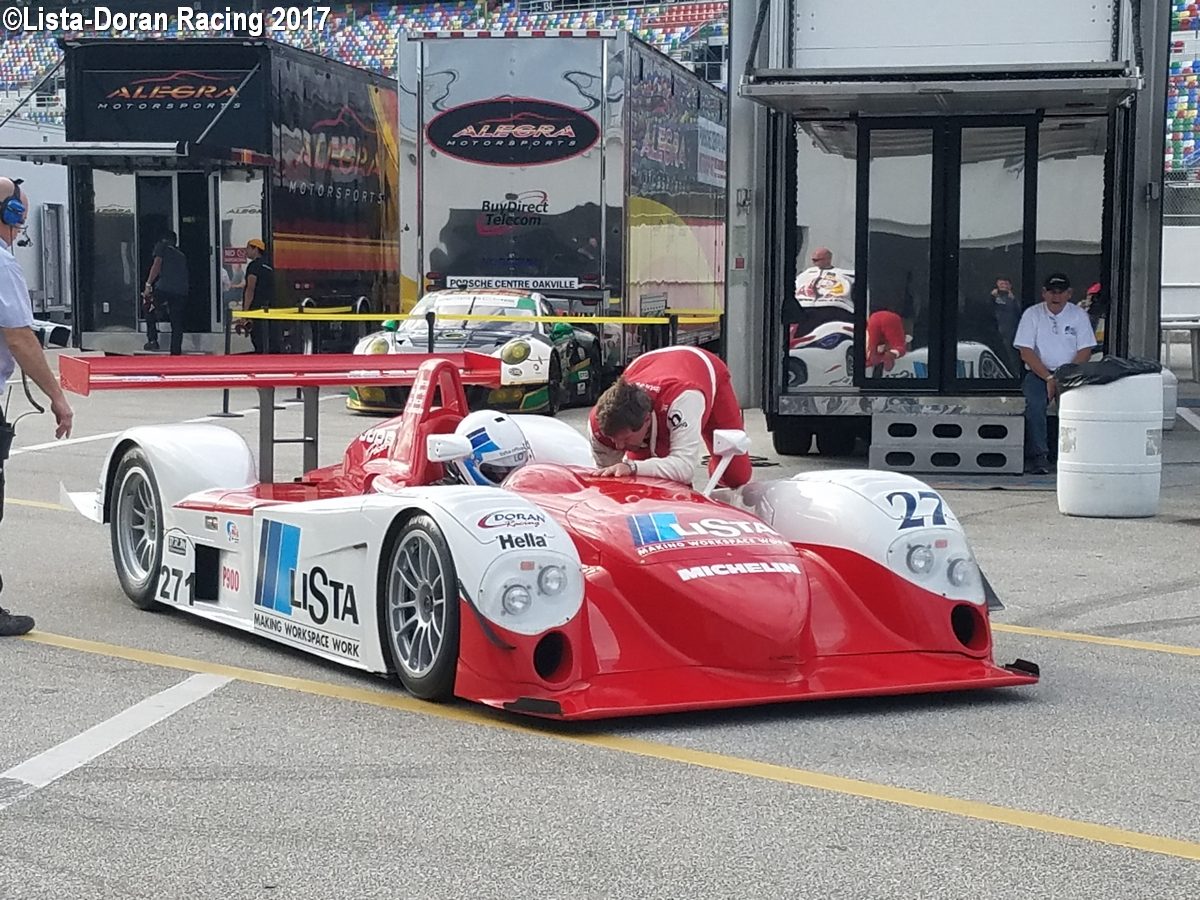

Andy Wallace led from the start for Dyson (the BMWs were absent as they prepared to win Le Mans), but was called in during the first caution period, which turned out to be the wrong move. vdP and David Brabham (this was the debut of the mighty Panoz roadster) started well back, after some kind of ‘qualifying times withdrawn’ nonsense – and while the Panoz was a handful during its first run ever on full tanks, the Rafanelli entry was going like a dream. vdP picked his way through virtually the whole field and took the lead, which set up a conclusion in which partner Mimmo Schiattarella saw off Didier Theys in the Doran Lista Ferrari, to win by 25 seconds.

The V12 Ferraris seemed handicapped by their restrictors in ’99, in ways that the V10 Judd-powered R&S wasn’t. The commentators (rather unfairly) suggested that the V10 might fail in that last stint – but it was as simple as an over-filled oil tank blowing out the excess.

I wonder if Dyson Racing ever considered converting their cars to Judd power? Kevin Doran eventually did just that with his 333 Ferrari, creating the famous ‘Fudd’.

EF-R / Leitzinger finished third, as their points tally grew steadily, while Don’s LMP Roadster S finished a fine fifth on its debut.

The Schumacher and Snow Porsches had a great race in GTS (the former just winning), while PTG won GT – with none other than Johannes van Overbeek partnering Brian Cunningham. Is Johannes the longest serving driver in the series?

Don’s series. That was a sad day, back in September last year, when we learned that Don had passed away. The greatest benefactor that any series has ever had? Did he ever get annoyed if his cars didn’t win? To my knowledge, he never did. He genuinely seemed to simply love a great event, his event, attended by huge numbers of fans.

I know how much he loved it when the orange, Lawrence Tomlinson, Panoz Esperante won its class at Le Mans: when his bellowing (prototype) monsters beat the Audis, he was clearly thrilled – but he didn’t seem to demand race wins, the way others might.

My Don Panoz story came a few years later, in the spring of 2004. For the full story, you’ll have to wait until my book is launched (I think enough years have elapsed for the tale to be told), but in essence, Don was grateful for a story that I didn’t write. Don and Scott Atherton approached me in the Monza press room (it was the ELMS race), and Don expressed his personal thanks to me. I was touched!

Incidentally, I’m hoping the book will be launched at Brands Hatch on May 25. Anyone who reads this is invited to attend – and I’m sure you’ll announce it on DDC nearer the time, once it’s confirmed. Thanks in advance for that!

Right, back to 1999. Don’s cars took a 1-2 at Mosport (Tom Kjos had taken over reporting duties – and what a great job he did over the years), won again at Portland, lucked into the win at the second Petit Le Mans (that man Wallace joined regulars Brabham and Bernard), lost out at Laguna Seca – and all the while, EF-R had been racking up the points.

The proposed San Diego race didn’t happen, replaced by a fanless Las Vegas – and I was determined to be there. With the help of Brooksie, Kerry Morse and Cort Wagner, the trip was on.

The TV highlights of that race don’t match my memories in one, significant respect… Having qualified eighth and ninth, the Dyson entries experienced very different fortunes. AWOL and Butch in #20 were out after just 22 laps with gearbox trouble, but James was EF-R’s ‘wingman’ in #16. In the opening exchanges, my memory is James really going for it – but the highlights on youtube don’t really show that. I can still picture the Riley & Scott on a charge, its driver all ‘elbows out’ as he battled to give Elliott a chance of the title later on. Jean-Marc Gounon was almost as boisterous in the DAMS Lola: it was fantastic entertainment.

But #16 then suffered with a fuel pressure problem, and it looked as though the Panoz drivers (B & B) would be title winners – until their engine failed with 17 laps left. BMW finished 1-2, but EF-R limped home sixth and he was the drivers’ champion.

I surprised James Weaver by appearing in the pit-lane wearing his old, ’96, BPR Gulf overalls (lent to me by Kerry Morse – I’ve no idea how he got hold of them).

“You’re wearing my overalls!” said an otherwise speechless James.

Oh, the Rafanelli R&S was first retirement, unfortunately, with overheating. Was it the right move to park that car and race a Lola in 2000?

Cort Wagner was the champ in GT, while Olivier Beretta took the honours in GTS, in an ORECA Viper, a car that I haven’t mentioned in this tale (Le Mans was the initial priority). Wagner and Muller won their class at Las Vegas, with the red and white Vipers 1-2 in GTS.

My last thought here is connected to youtube, again. Something I’ve been getting interested in is the whole 9/11 thing. I’m not going to ram my thoughts down your throat – but I would like to suggest that you look up Rebekah Roth, Christopher Bollyn, Barbara Honegger and / or Richard Gage, and listen to some of their views on what really happened in September 2001. The more you find out, the more extraordinary that tale becomes. If you find that lot interesting, you might also consider looking up ‘Operation Mockingbird’.

Now, I’ve got to go and look up my favourite ALMS race on youtube: Laguna Seca in 2005. I think that was the one when John Hindhaugh ‘did his nut’ when the overall leaders came up to lap the scrapping Corvettes and Aston Martins. Great memories (or just plain “living in the past”).

Crackers out.

Autumn or Fall as the locals would say is a very agreeable time to be in California’s Monterey Peninsula. This weekend the 2018 Intercontinental GT Challenge will reach its climax after a season of classic endurance GT races. SRO has history at the fantastic Laguna Seca track dating back to its earliest days.

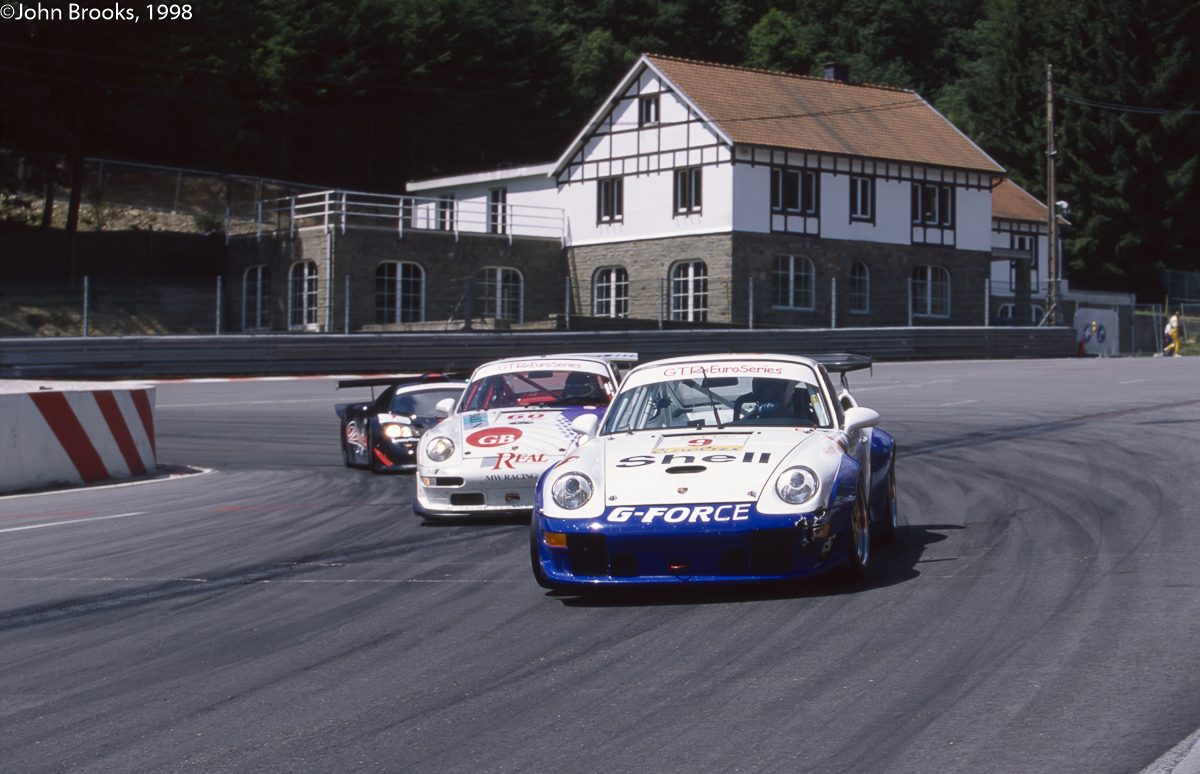

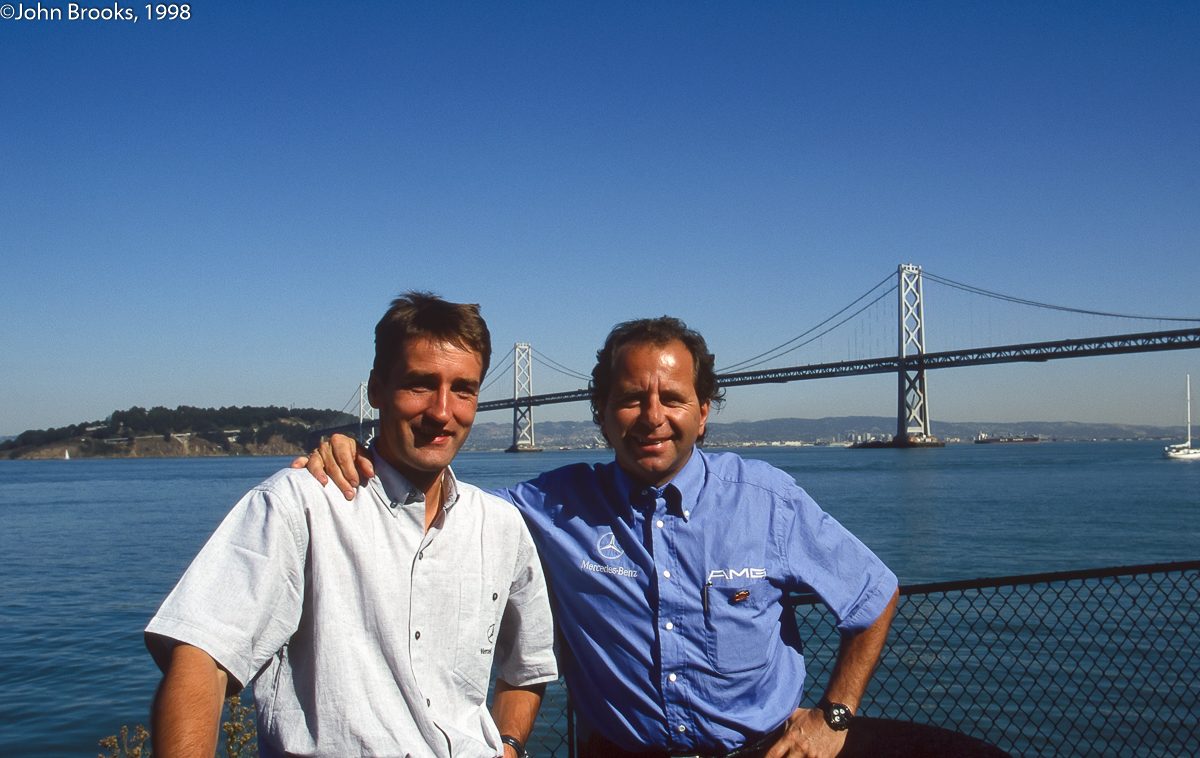

Autumn or Fall as the locals would say is a very agreeable time to be in California’s Monterey Peninsula. This weekend the 2018 Intercontinental GT Challenge will reach its climax after a season of classic endurance GT races. SRO has history at the fantastic Laguna Seca track dating back to its earliest days.  Some 20 years ago the final round of the 1998 FIA GT Championship, was held at Laguna Seca. In the top GT1 class it was scheduled to be a classic encounter between the veteran champion, Klaus Ludwig and the bright star emerging to ascendancy, Bernd Schneider. Yes of course they had co-drivers, Ricardo Zonta and Mark Webber, but despite the obvious talent and potential of that pair all eyes were on the two Germans of different generations. Schneider had taken the title in 1997 and had looked favourite to repeat this for most of the 1998 season.

Some 20 years ago the final round of the 1998 FIA GT Championship, was held at Laguna Seca. In the top GT1 class it was scheduled to be a classic encounter between the veteran champion, Klaus Ludwig and the bright star emerging to ascendancy, Bernd Schneider. Yes of course they had co-drivers, Ricardo Zonta and Mark Webber, but despite the obvious talent and potential of that pair all eyes were on the two Germans of different generations. Schneider had taken the title in 1997 and had looked favourite to repeat this for most of the 1998 season. What added spice to the contest was that they were both driving for the AMG Mercedes team, for the majority of the season in the all-conquering Mercedes-Benz CLK-LM. Approaching the decisive race, the score sheet showed Ludwig and Zonta ahead of their rivals by four points, the margin between first and second place on track. However, Schneider and Webber had racked up five wins to four, so if the points tally was equal after Laguna Seca they would be champions on the basis of more race wins. It was a case of the winner takes it all and second place would be nowhere.

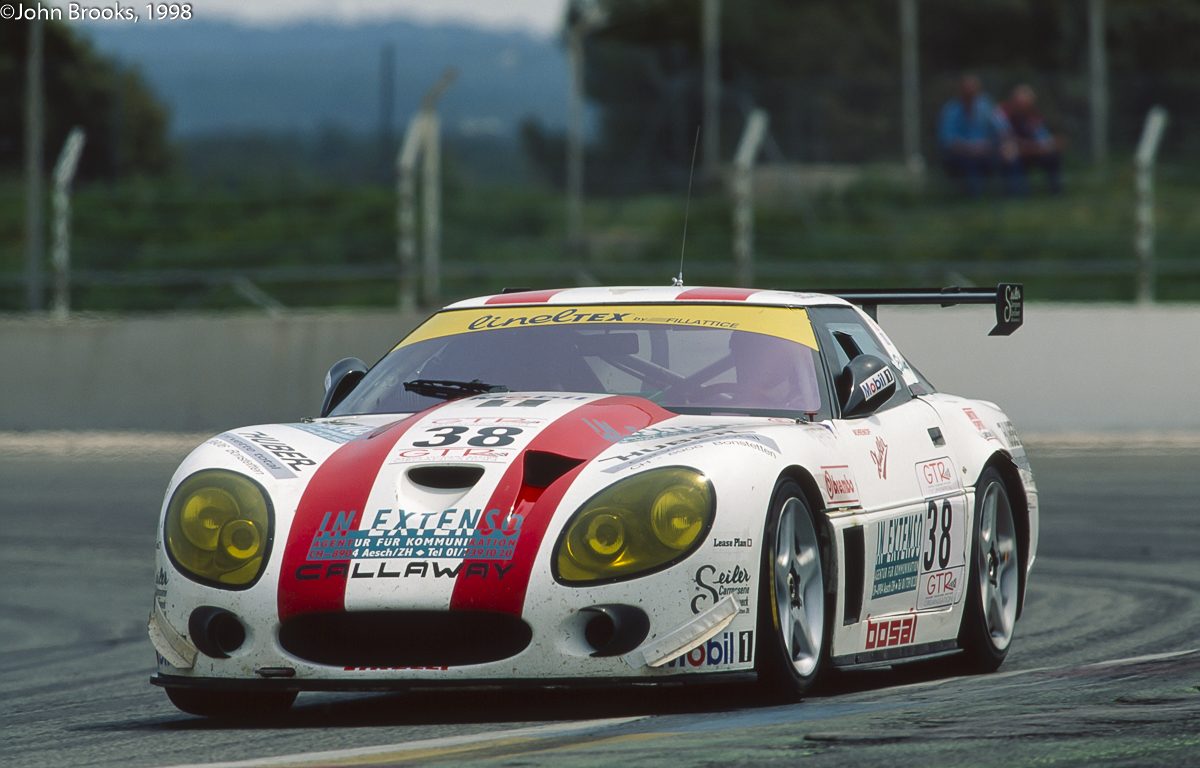

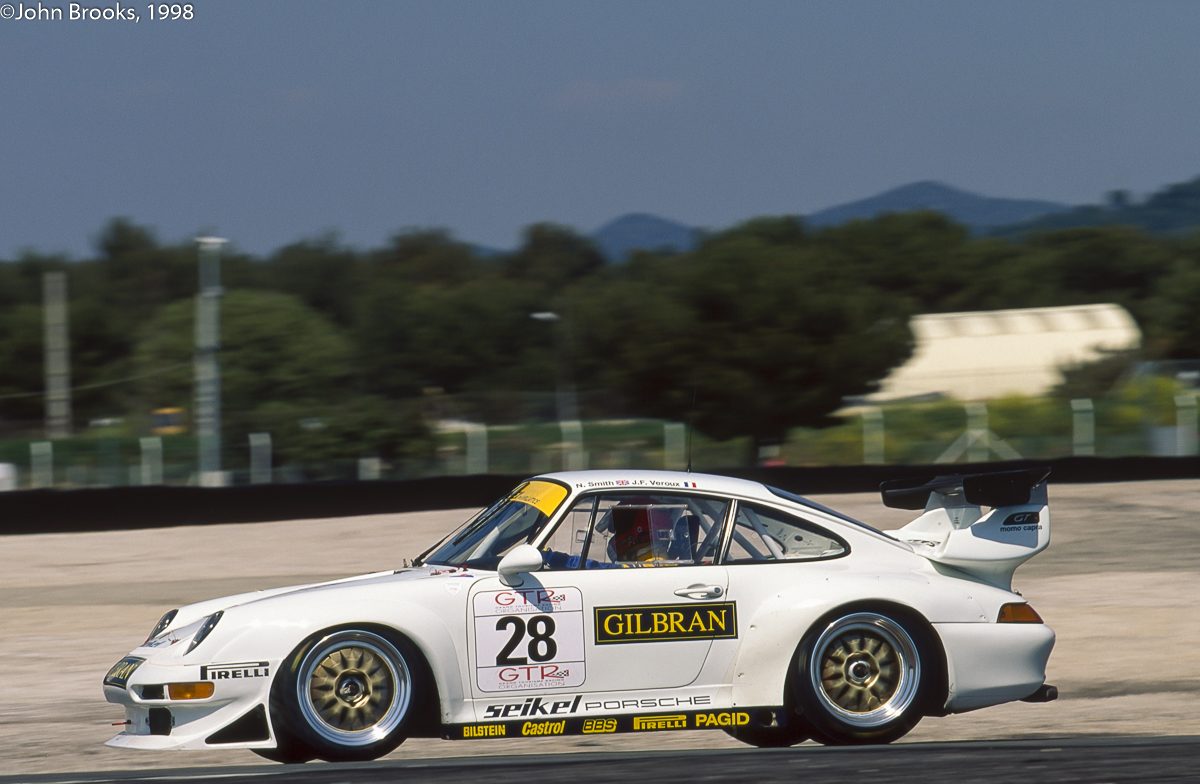

What added spice to the contest was that they were both driving for the AMG Mercedes team, for the majority of the season in the all-conquering Mercedes-Benz CLK-LM. Approaching the decisive race, the score sheet showed Ludwig and Zonta ahead of their rivals by four points, the margin between first and second place on track. However, Schneider and Webber had racked up five wins to four, so if the points tally was equal after Laguna Seca they would be champions on the basis of more race wins. It was a case of the winner takes it all and second place would be nowhere. The GT2 class was a complete contrast to this close contest in GT1. The Oreca Chrysler Viper team dominated proceedings, winning eight out of the nine rounds already run. Olivier Beretta and Pedro Lamy had grabbed the Drivers’ Title with seven victories, Monterey was expected to be more of the same. Could either the Roock Racing Porsches or Cor Euser’s Marcos challenge the Viper’s hegemony?

The GT2 class was a complete contrast to this close contest in GT1. The Oreca Chrysler Viper team dominated proceedings, winning eight out of the nine rounds already run. Olivier Beretta and Pedro Lamy had grabbed the Drivers’ Title with seven victories, Monterey was expected to be more of the same. Could either the Roock Racing Porsches or Cor Euser’s Marcos challenge the Viper’s hegemony? 1998 was an almost perfect season for the AMG Mercedes squad. The only hiccup had come during the Le Mans 24 Hours when both cars went out early after suffering engine failure. A seal in the power-steering hydraulic pump failed and that trivial fault fatally damaged the engine. It was a most un-Mercedes moment as otherwise they were in a different league to their closest and only serious competitor, Porsche AG’s 911 GT1 98.

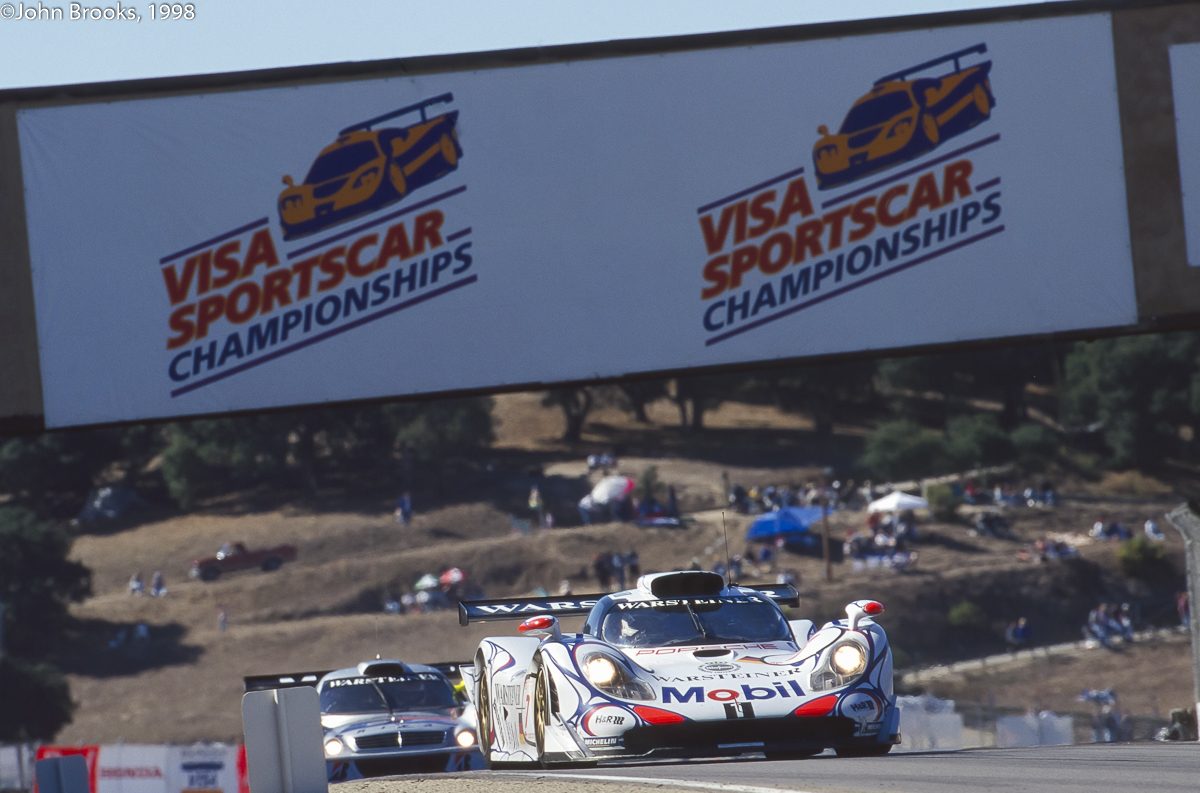

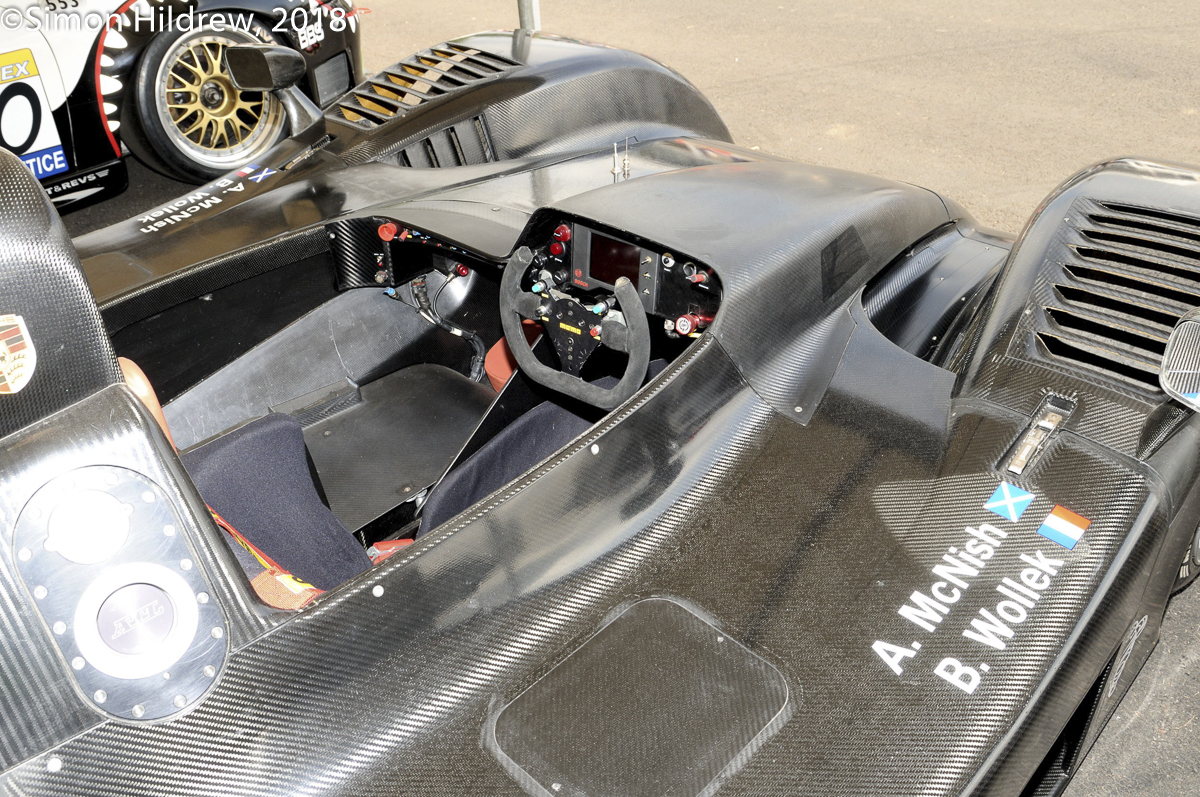

1998 was an almost perfect season for the AMG Mercedes squad. The only hiccup had come during the Le Mans 24 Hours when both cars went out early after suffering engine failure. A seal in the power-steering hydraulic pump failed and that trivial fault fatally damaged the engine. It was a most un-Mercedes moment as otherwise they were in a different league to their closest and only serious competitor, Porsche AG’s 911 GT1 98. In reality the Porsche was only a threat at certain kinds of circuits where the disadvantage of their turbocharged engines as regulated under the FIA GT1 rules package was not a factor. And even then, it was almost always Allan McNish who was able to challenge the Mercedes duo, we would grow accustomed to the electric pace of the Scot in the following decade, but it was something of an eye opener in 1998.

In reality the Porsche was only a threat at certain kinds of circuits where the disadvantage of their turbocharged engines as regulated under the FIA GT1 rules package was not a factor. And even then, it was almost always Allan McNish who was able to challenge the Mercedes duo, we would grow accustomed to the electric pace of the Scot in the following decade, but it was something of an eye opener in 1998. Adding even more spice to the contest was the announcement by Ludwig that he would retire from motor sport after the race in Monterey. His career had included three victories at Le Mans and five DTM titles, could he add the FIA GT Championship to the list? Klaus certainly was motivated, and said before the race, “Laguna Seca is one of the tracks I love the best. It’s a demanding track and an exciting track – the Corkscrew, in Europe, impossible! To win there would be very special for me.”

Adding even more spice to the contest was the announcement by Ludwig that he would retire from motor sport after the race in Monterey. His career had included three victories at Le Mans and five DTM titles, could he add the FIA GT Championship to the list? Klaus certainly was motivated, and said before the race, “Laguna Seca is one of the tracks I love the best. It’s a demanding track and an exciting track – the Corkscrew, in Europe, impossible! To win there would be very special for me.”  Ludwig was not the only one departing the GT scene, Ricardo Zonta was bound for Formula One, another Brazilian on the conveyor-belt of talent that started with Emmerson Fittipaldi and continued through Piquet, Senna, Barrichello and Massa amongst many others.

Ludwig was not the only one departing the GT scene, Ricardo Zonta was bound for Formula One, another Brazilian on the conveyor-belt of talent that started with Emmerson Fittipaldi and continued through Piquet, Senna, Barrichello and Massa amongst many others. However, there was still a Championship to be decided. Most Europeans like myself imagine that California is a place of sunshine and beaches, blondes and brunettes of either sex, all tanned, forever young. So, it was something of a shock arriving at the track in anticipation of Saturday Morning’s Qualifying session to conditions usually found at the Nürburgring or Spa, torrential rain. The first session was stopped after 15 minutes as a river of mud was blocking the Corkscrew, not quite how I imagined the weather would be on the West Coast.

However, there was still a Championship to be decided. Most Europeans like myself imagine that California is a place of sunshine and beaches, blondes and brunettes of either sex, all tanned, forever young. So, it was something of a shock arriving at the track in anticipation of Saturday Morning’s Qualifying session to conditions usually found at the Nürburgring or Spa, torrential rain. The first session was stopped after 15 minutes as a river of mud was blocking the Corkscrew, not quite how I imagined the weather would be on the West Coast. The afternoon’s conditions were much better and the advantage swung Ludwig’s way courtesy of Zonta. The Brazilian’s pole position lap of 1m16.154s was 0.434 seconds faster than Schneider’s best. Afterwards Ricardo explained. “My qualifying lap was really good but not without a problem. Because I experienced a little brake balance problem, I got off-line in the last corner where it was a little wet. That might have cost me some time.”

The afternoon’s conditions were much better and the advantage swung Ludwig’s way courtesy of Zonta. The Brazilian’s pole position lap of 1m16.154s was 0.434 seconds faster than Schneider’s best. Afterwards Ricardo explained. “My qualifying lap was really good but not without a problem. Because I experienced a little brake balance problem, I got off-line in the last corner where it was a little wet. That might have cost me some time.” In GT2 the Viper effort was reduced to one car after David Donohue crashed out on Friday. He hit the wall hard as a result of brake failure, the car caught fire and was too badly damaged for any immediate repair.

In GT2 the Viper effort was reduced to one car after David Donohue crashed out on Friday. He hit the wall hard as a result of brake failure, the car caught fire and was too badly damaged for any immediate repair. Class Pole was grabbed by a very determined Stéphane Ortelli in his Roock Racing Porsche 911 GT2 with a 1:24.851 lap, less than a tenth of second advantage over Cor Euser’s Marcos LM 600 who was fractions faster than Beretta’s Viper. This could be a race to match the GT1 battle, or so we hoped.

Class Pole was grabbed by a very determined Stéphane Ortelli in his Roock Racing Porsche 911 GT2 with a 1:24.851 lap, less than a tenth of second advantage over Cor Euser’s Marcos LM 600 who was fractions faster than Beretta’s Viper. This could be a race to match the GT1 battle, or so we hoped. After the traditional end-of-term drivers’ photo Klaus was presented with a lump of the track as a memento of his final race, it seemed a very Californian thing to do.

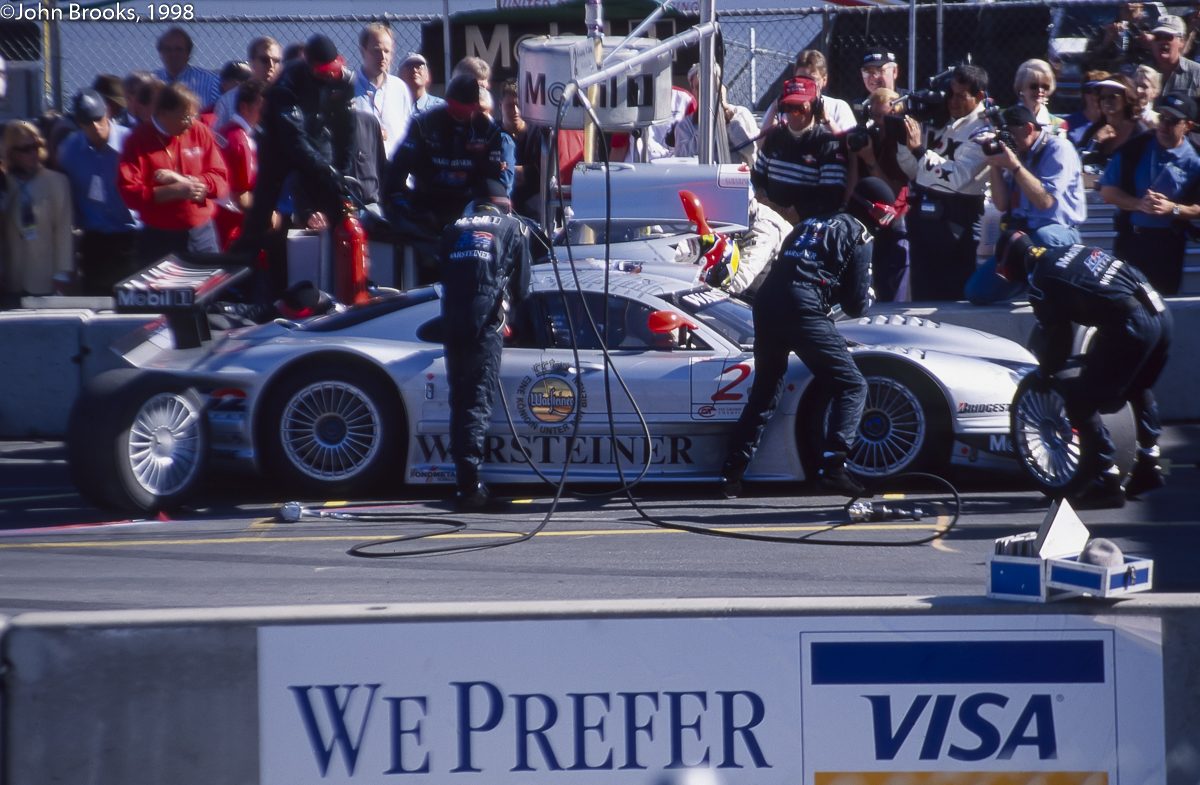

After the traditional end-of-term drivers’ photo Klaus was presented with a lump of the track as a memento of his final race, it seemed a very Californian thing to do. AMG Mercedes had the front row to themselves, who would emerge from Turn One in the lead, Schneider or Ludwig? Everyone held their breath but in the end the veteran got the best start and quickly pulled away from his rival.

AMG Mercedes had the front row to themselves, who would emerge from Turn One in the lead, Schneider or Ludwig? Everyone held their breath but in the end the veteran got the best start and quickly pulled away from his rival. In any case Bernd had his mirrors full of a Porsche with McNish making a nuisance of himself, even passing the Mercedes after a few laps.

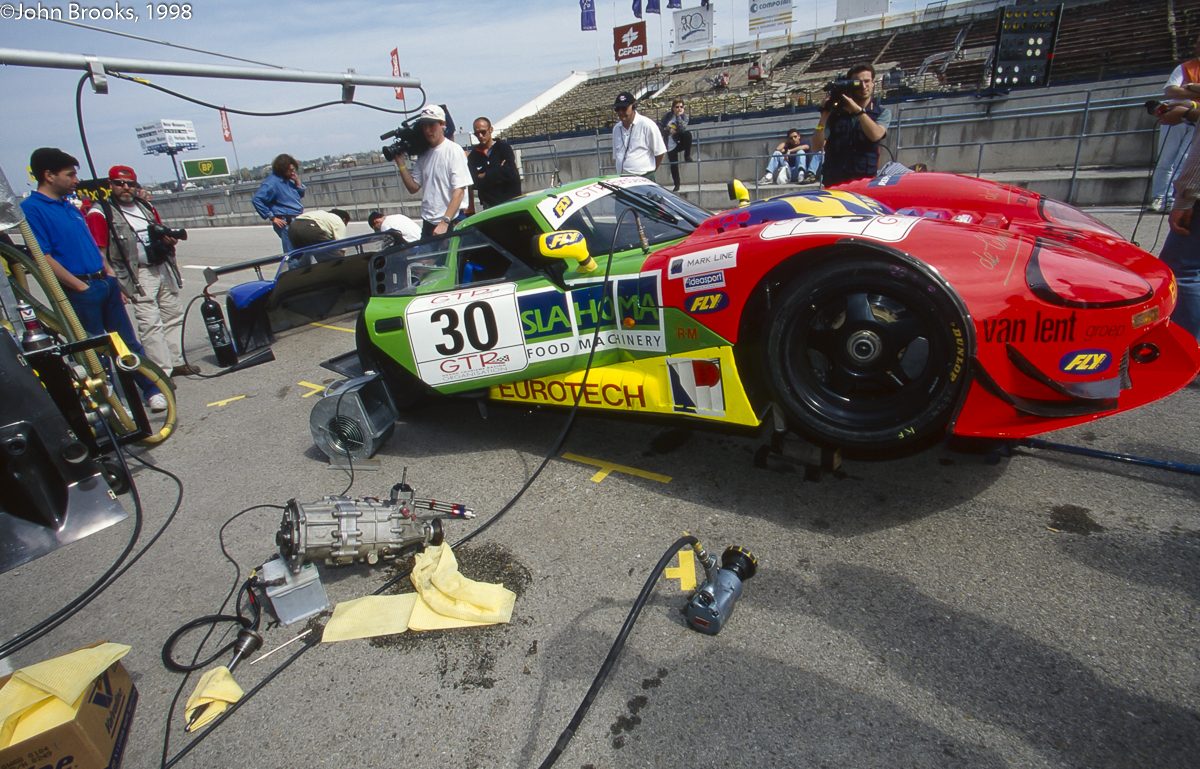

In any case Bernd had his mirrors full of a Porsche with McNish making a nuisance of himself, even passing the Mercedes after a few laps. GT2 also saw a fierce tussle for the lead in opening laps before the natural order of things asserted itself with Beretta grabbing the lead. Two of the major challengers to the all-conquering Viper both retired with gearbox failure after just seven laps, that was the end of Jan Lammers in the Konrad Porsche and also Claudia Hürtgen in the 911 she shared with Ortelli. A few laps later and the Marcos was out. Also with transmission woes.

GT2 also saw a fierce tussle for the lead in opening laps before the natural order of things asserted itself with Beretta grabbing the lead. Two of the major challengers to the all-conquering Viper both retired with gearbox failure after just seven laps, that was the end of Jan Lammers in the Konrad Porsche and also Claudia Hürtgen in the 911 she shared with Ortelli. A few laps later and the Marcos was out. Also with transmission woes. Ludwig had his own dramas to contend with while negotiating his way through the traffic. William Langhorne in the Stadler GT2 Porsche was having a spirited contest with Michel Neugarten in his Elf Haberthur example, swapping positions round the sweeping track. The American was fully concentrating on the car in front so did not see Ludwig dive underneath him at Turn Three. The result was a heavy side impact that nearly put Klaus off the tarmac but somehow, he gathered himself together and raced on at full speed. Langhorne crashed out the following lap at the Corkscrew, something broke he maintained.

Ludwig had his own dramas to contend with while negotiating his way through the traffic. William Langhorne in the Stadler GT2 Porsche was having a spirited contest with Michel Neugarten in his Elf Haberthur example, swapping positions round the sweeping track. The American was fully concentrating on the car in front so did not see Ludwig dive underneath him at Turn Three. The result was a heavy side impact that nearly put Klaus off the tarmac but somehow, he gathered himself together and raced on at full speed. Langhorne crashed out the following lap at the Corkscrew, something broke he maintained. Schneider also got rid of the McNish problem around this point, the clutch failed on the Porsche stranding the Scot out on the far side of the circuit. It would be a straight fight for victory for the #1 and #2 Mercedes. Schneider then dived into the pits, fuel only, no fresh Bridgestones.

Schneider also got rid of the McNish problem around this point, the clutch failed on the Porsche stranding the Scot out on the far side of the circuit. It would be a straight fight for victory for the #1 and #2 Mercedes. Schneider then dived into the pits, fuel only, no fresh Bridgestones. A lap later Ludwig was in, then out of the car, Zonta taking new rubber. He managed to stall the CLK-LM as he left the pits, all of which gave a handy advantage back to Schneider.

A lap later Ludwig was in, then out of the car, Zonta taking new rubber. He managed to stall the CLK-LM as he left the pits, all of which gave a handy advantage back to Schneider. Bernd was looking certain to take the title but then lost a load of time stuck behind Jörg Müller in the other factory Porsche 911 GT1 98. Müller was determined to not go a lap down on the leader, hoping that the deployment of a Safety Car would give him the chance to catch up to the front. Eventually Müller ran wide at the first turn, allowing Schneider to pass, though he was furious at his fellow German. The gap was around the 12 second mark but this might not be enough to guarantee victory.

Bernd was looking certain to take the title but then lost a load of time stuck behind Jörg Müller in the other factory Porsche 911 GT1 98. Müller was determined to not go a lap down on the leader, hoping that the deployment of a Safety Car would give him the chance to catch up to the front. Eventually Müller ran wide at the first turn, allowing Schneider to pass, though he was furious at his fellow German. The gap was around the 12 second mark but this might not be enough to guarantee victory. The second stints ended and into the pits came Schneider to hand over to his Aussie co-driver who also received a new set of tyres. This would put Webber behind Zonta on the road as it was expected that his stop would be a fuel only affair and so it proved. The AMG Mercedes management had anxious moments after both of their cars left the pits for the final time. Both fell off the track at Turn Three where oil had been deposited by a back marker, both cars just missed hitting the wall by a fraction, it could have been a disaster.

The second stints ended and into the pits came Schneider to hand over to his Aussie co-driver who also received a new set of tyres. This would put Webber behind Zonta on the road as it was expected that his stop would be a fuel only affair and so it proved. The AMG Mercedes management had anxious moments after both of their cars left the pits for the final time. Both fell off the track at Turn Three where oil had been deposited by a back marker, both cars just missed hitting the wall by a fraction, it could have been a disaster. Zonta had a lead of 16 seconds but Webber got his head down and chipped away taking a second here, a second there. The #8 Porsche intervened again, this time it was Uwe Alzen’s turn to hold up the #1 Mercedes for a lap or two. Eventually Weber dived down the inside at the first turn and once again the was contact as the Porsche was muscled out of the way but he was through and the chase was back on.

Zonta had a lead of 16 seconds but Webber got his head down and chipped away taking a second here, a second there. The #8 Porsche intervened again, this time it was Uwe Alzen’s turn to hold up the #1 Mercedes for a lap or two. Eventually Weber dived down the inside at the first turn and once again the was contact as the Porsche was muscled out of the way but he was through and the chase was back on. Webber posted a time of 1:19.094, setting a new GT record, would it be enough? The gap came down to ten seconds but the time ran out for the chasing Mercedes and Zonta crossed the line 10.8 seconds ahead – Ludwig and Zonta were Champions, the fairy tale had come true.

Webber posted a time of 1:19.094, setting a new GT record, would it be enough? The gap came down to ten seconds but the time ran out for the chasing Mercedes and Zonta crossed the line 10.8 seconds ahead – Ludwig and Zonta were Champions, the fairy tale had come true. There was no fairy tale in GT2, in fact the whole affair was something of a damp squib. The race was a walk over for Beretta and Lamy, who scored their eight class win of the season, ending up over a lap in front of the second Roock Racing 911 GT2, driven by Bruno Eichmann and Mike Hezemans. The final spot on the podium want to another 911 GT2, driven by Michael Trunk and Bernhard Müller.

There was no fairy tale in GT2, in fact the whole affair was something of a damp squib. The race was a walk over for Beretta and Lamy, who scored their eight class win of the season, ending up over a lap in front of the second Roock Racing 911 GT2, driven by Bruno Eichmann and Mike Hezemans. The final spot on the podium want to another 911 GT2, driven by Michael Trunk and Bernhard Müller. Schneider showed grace in defeat, he is, and always was, a class act. “Failing to win the title after 10 races by just 10 seconds shows how tough we raced for the Drivers’ Championship this season. Although Mark and I didn’t manage to win the Championship, I’m glad for the team. Congratulations to my old friend Klaus, who deserves to end his career as Champion.”

Schneider showed grace in defeat, he is, and always was, a class act. “Failing to win the title after 10 races by just 10 seconds shows how tough we raced for the Drivers’ Championship this season. Although Mark and I didn’t manage to win the Championship, I’m glad for the team. Congratulations to my old friend Klaus, who deserves to end his career as Champion.” Mark later reflected on the result in his excellent autobiography ‘Aussie Grit’. “So, the end result was second place in the FIA GT Championship by a margin of eight points. My disappointment was tempered by happiness for Klaus, since that was his last year in racing, but I also felt it had been a little unfair on Bernd. His partner came from Formula Ford and F3, whereas Ricardo arrived as the new F3000 champion to partner Klaus and was already getting test drives in Formula 1. I could go toe-to-toe with them most times but sometimes I struggled, partly because it was Bernd’s car, basically, and he had it set up as he wanted it, and partly through sheer lack of experience.”

Mark later reflected on the result in his excellent autobiography ‘Aussie Grit’. “So, the end result was second place in the FIA GT Championship by a margin of eight points. My disappointment was tempered by happiness for Klaus, since that was his last year in racing, but I also felt it had been a little unfair on Bernd. His partner came from Formula Ford and F3, whereas Ricardo arrived as the new F3000 champion to partner Klaus and was already getting test drives in Formula 1. I could go toe-to-toe with them most times but sometimes I struggled, partly because it was Bernd’s car, basically, and he had it set up as he wanted it, and partly through sheer lack of experience.”  Zonta had this to say after the race. “This was a real tough title fight. I had to give it my all to keep the gap to Mark Webber wide enough to make it. The fact that we both went off because of oil on the track shows how close to the limit we were. I’m really happy about the title and that I could win it together with Klaus.”

Zonta had this to say after the race. “This was a real tough title fight. I had to give it my all to keep the gap to Mark Webber wide enough to make it. The fact that we both went off because of oil on the track shows how close to the limit we were. I’m really happy about the title and that I could win it together with Klaus.” The retiring Champion had the last word. “I’m extremely happy about the Championship. This was a sensational achievement by the team, and my co-driver Ricardo is the best I could have asked for. I want to thank especially Norbert Haug and Hans Werner Aufrecht, who brought me back to AMG Mercedes.”

The retiring Champion had the last word. “I’m extremely happy about the Championship. This was a sensational achievement by the team, and my co-driver Ricardo is the best I could have asked for. I want to thank especially Norbert Haug and Hans Werner Aufrecht, who brought me back to AMG Mercedes.”

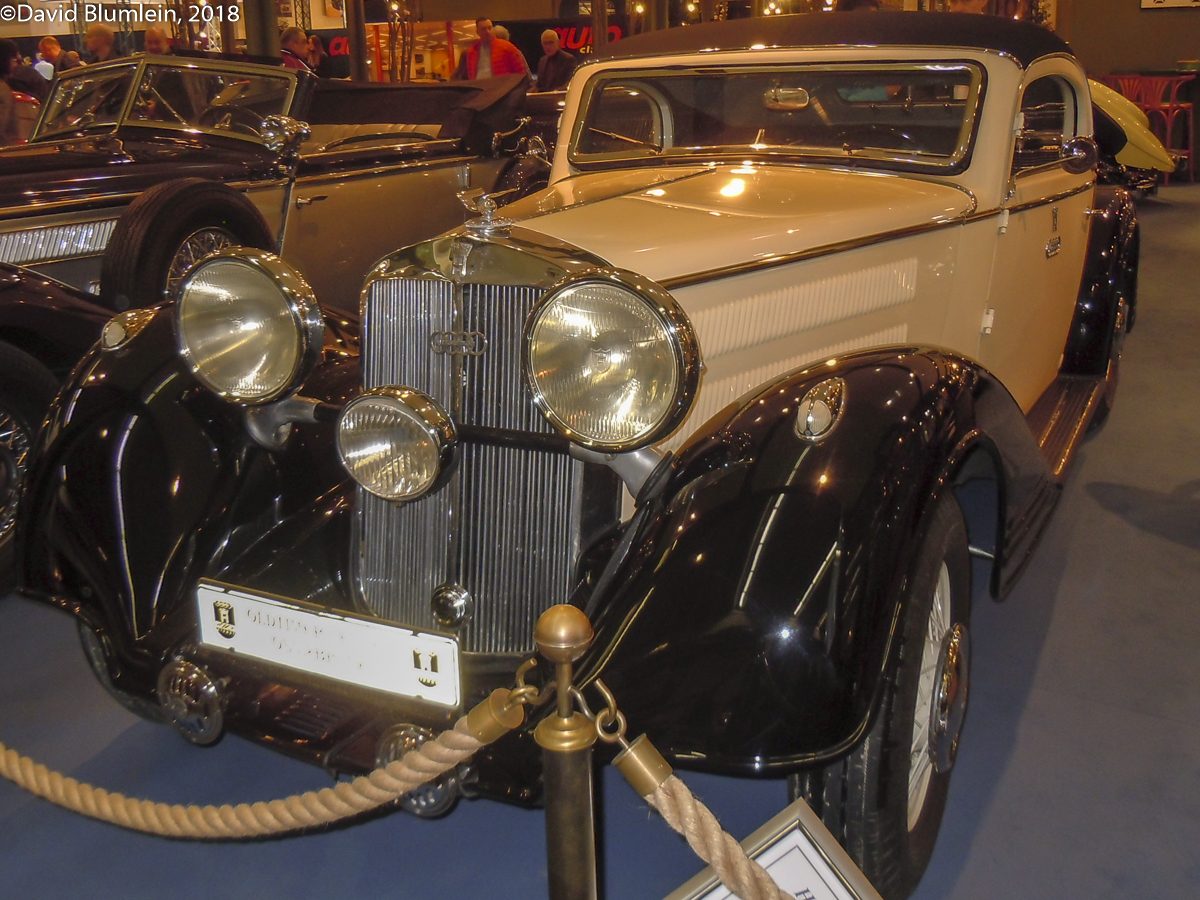

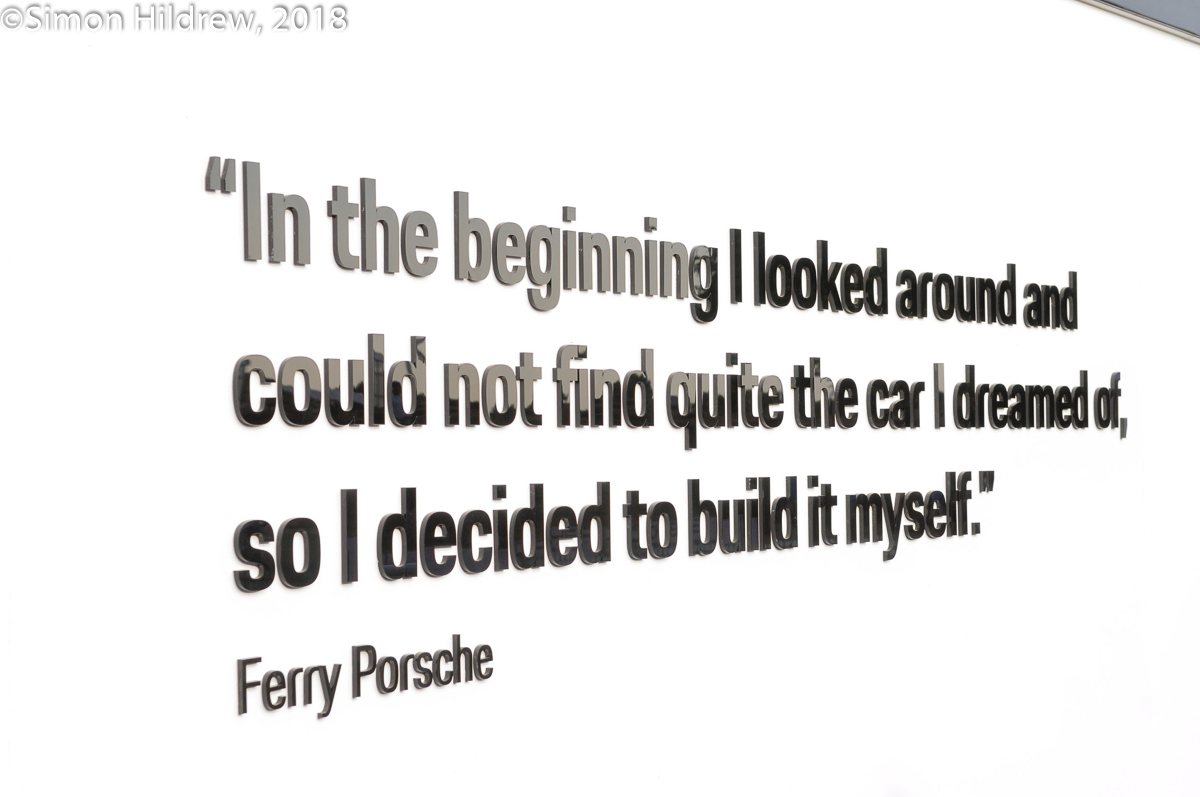

Take the Festival of Speed for example, I received a mountain of great photos from our resident lens-meister, Simon Hildrew. These arrived in the middle of a deadline or three, all urgent, well aren’t they all?

Take the Festival of Speed for example, I received a mountain of great photos from our resident lens-meister, Simon Hildrew. These arrived in the middle of a deadline or three, all urgent, well aren’t they all?