Most of you will know that Petit Le Mans runs this weekend, bringing down the curtain on the 2016 IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship. It is also the final performance in the career of the Daytona Prototype class. Who could have imagined back in 2003 that we would still have evolutions of this class of car racing for victories and titles?

The DPs, as the more polite members of the racing community referred to them, made their début at Daytona International Speedway running in the 2003 Rolex 24 Hours.

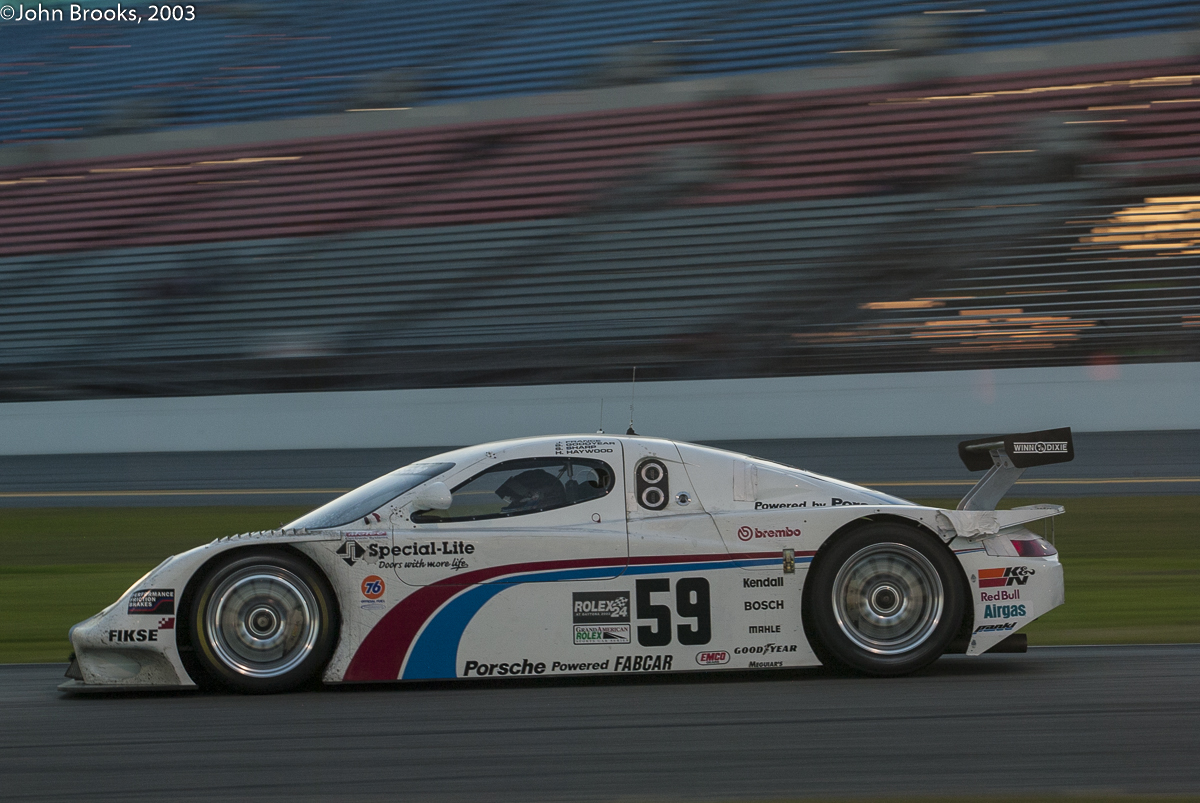

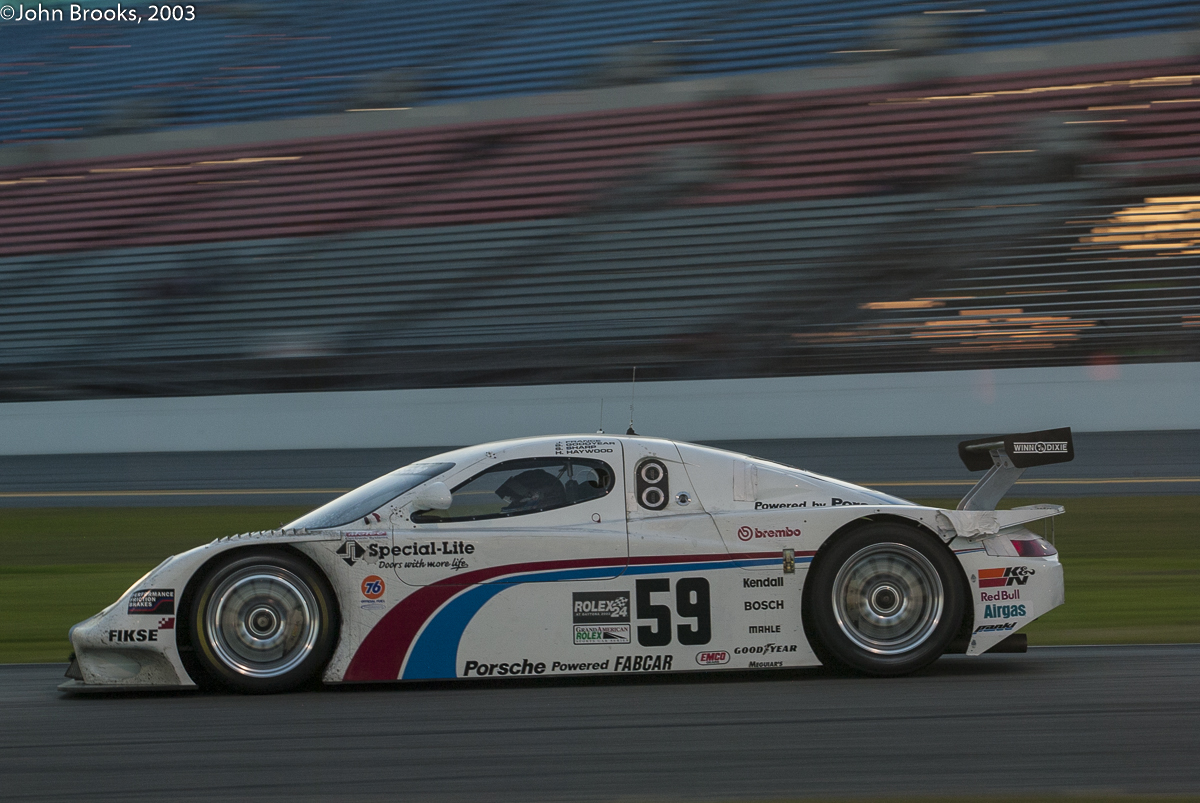

There were just six cars entered in the class with four chassis types and five different engine suppliers. Three of these were Fabcar FDSC/03s and two of these were entered by Brumos Racing and were, naturally, Porsche powered. #59 in the famous red, white and blue livery had Daytona 24 Hours legend, Hurley Haywood, leading the driving squad, with J. C. France and Indy Car hired guns, Scott Goodyear and Scott Sharp in support.

#58 had David Donohue, Mike Borkowski, Randy Pobst and Chris Bye behind the wheel. Brumos had an air of quiet confidence having had an extensive test program and a recent 27 hour test that all went as well could be expected.

Cegwa Sport entered a Toyota powered Fabcar for Darius Grala, Oswaldo Negri, Josh Rehm and Guy Cosmo.

Lined up against this trio were the Italian built Picchio BMW DP2 for Boris Said, Darren Law, Dieter Quester and Luca Riccitelli, entered by G & W Motorsports.

A familiar face at the Rolex was Kevin Doran and, although his team was not there to defend their 2002 crown, he had built the Doran Chevrolet JE4 for Bell Motorsport. It would be driven by Terry Borcheller, Forrest Barber, Didier Theys and Christian Fittipaldi. The team was on the back foot from the start as the project was late in completion and had virtually no testing, not the way to approach the Rolex 24.

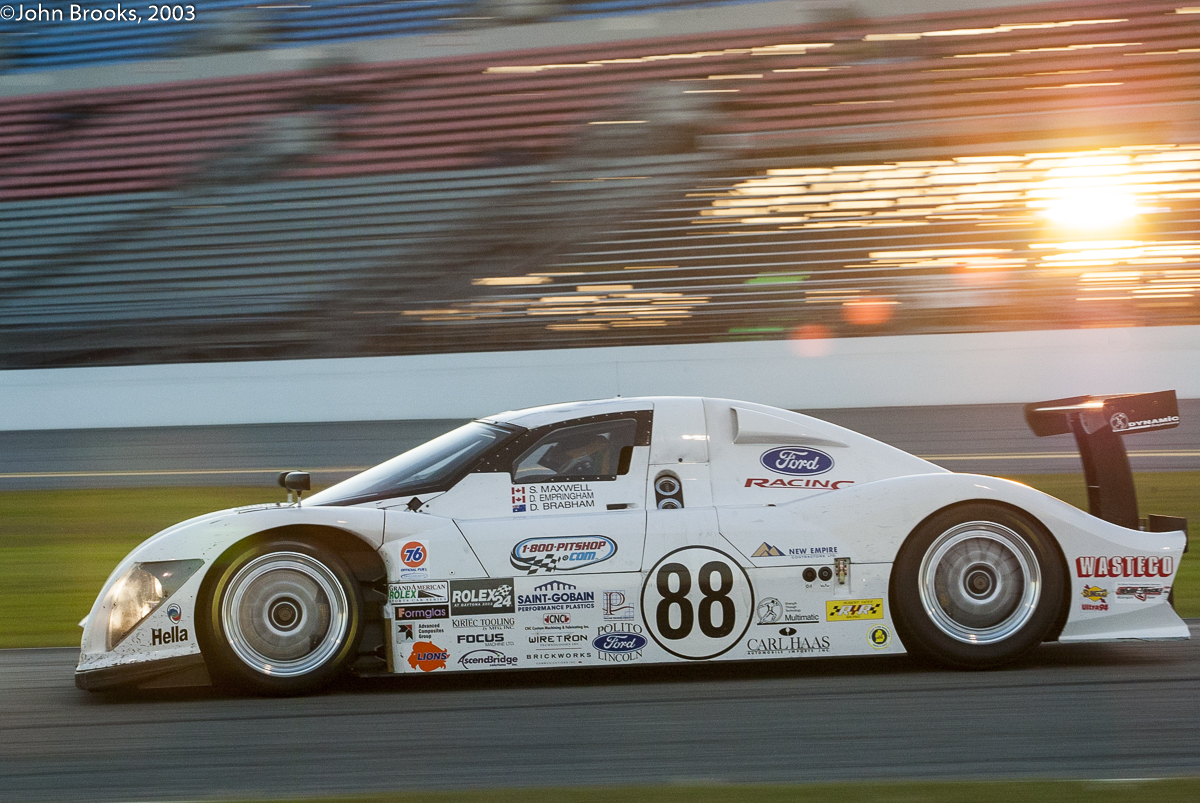

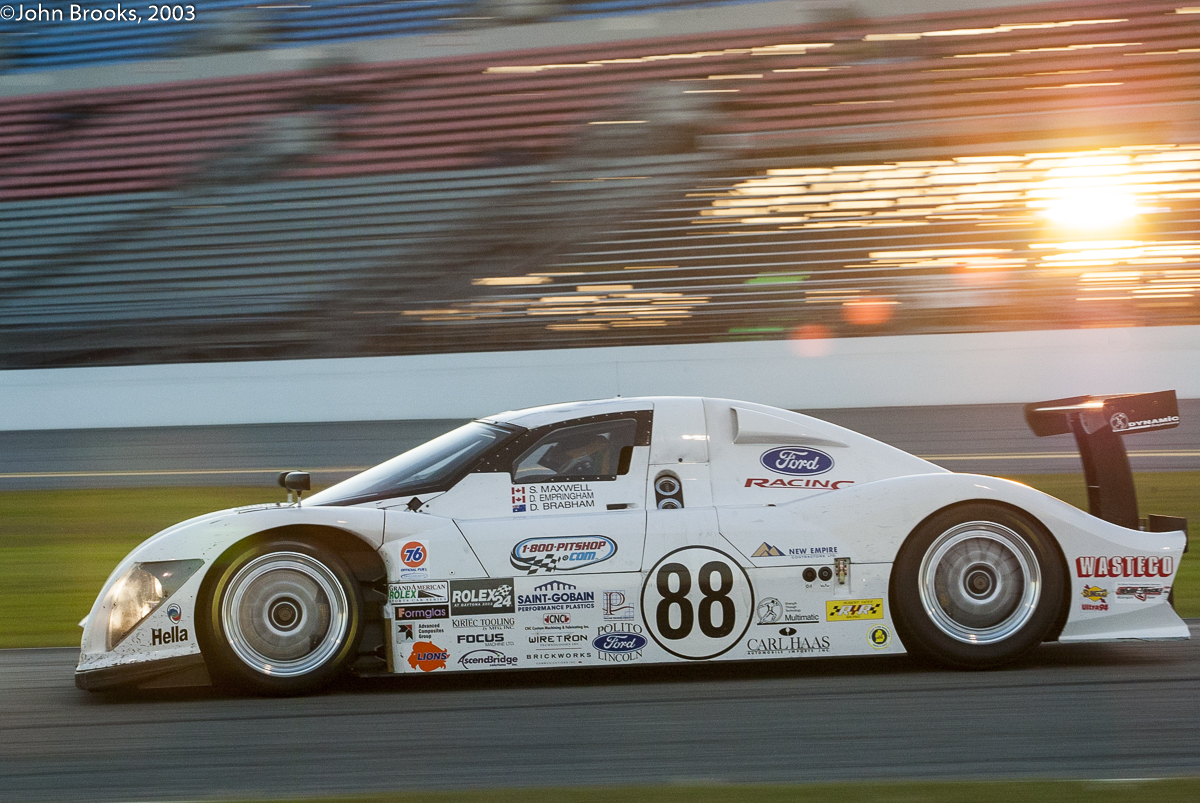

The final DP entered was the Multimatic Ford Focus MDP1 from Larry Holt’s Canadian outfit. He had regular team drivers Scott Maxwell and David Empringham with David Brabham completing the line up.

Just six cars in the “top class” and they were not even the fastest round the track at Daytona, that honour fell to Justin Bell and the Denhaag Motorsports Corvette running in the GTS class who posted a 1:49.394, over a second faster than the class leading Multimatic.

Let’s consider the situation, short of numbers, slower than the previous top prototype class, visually challenged and despised by legions of internet forum heroes, why did Grand-Am persist with this exercise in motor sport time travel? Tube frames in an era of carbon fibre, mocked as Proto-Turtles, what was the point? Indeed why did the mighty NASCAR empire devote time and resources to endurance racing when the core business was so successful and all consuming?

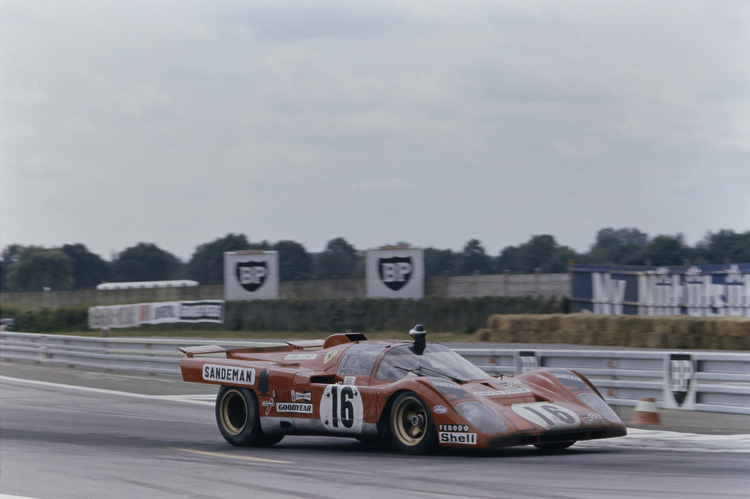

The final question is easiest to answer. Bill France Snr. had launched the Daytona sports car events back in 1962 and by 1966 that had morphed into a 24 hour that attracted a top international entry, Ferrari even had one their most famous Gran Turismos nicknamed after Daytona. So it has become part of the Daytona tradition to kick off the Speed Weeks with an endurance sports car race and by continuing the tradition it is honouring Bill Snr.’s legacy and memory. There is also the practical point that the Rolex 24 acts as a rehearsal for the Daytona 500 in getting the Speedway staff and other interested parties up to speed before the huge crowd arrives on race day for the opening event in the NASCAR calendar.

OK, why did the folks on West International Speedway Boulevard take the route of Daytona Prototypes? The answer is simple; cost, control and safety. Grand-Am was born out of the vacuum created by the demise of IMSA as run by Andy Evans and the subsequent rise of Don Panoz’ American Le Mans Series. This was perceived as a threat to hegemony of Daytona Beach in North American motor sport circles. Don owned Road Atlanta and Mosport and had manufacturers such as Audi, Porsche, Corvette and Viper beating a path to his door. He was serious and had the resources to match his ambition. The link with the ACO and Le Mans 24 Hours gave him and the ALMS instant credibility.

Something had to be done. In 2000 Grand-Am kicked off in the best possible manner with a great edition of the Rolex 24. Anyone interested in reading about that race might enjoy THIS

For the 2000 season Roger Edmondson, President of Grand-Am, attempted to forge links with John Mangoletsi’s Sports Racing World Cup from Europe to increase the number of prototypes available to populate the grid. This initiative failed, “Mango” could not deliver his side of the bargain, only a few cars made the trip across the Atlantic to the mid-season races at Daytona and Road America.

The Audi R8 prototype was rampant in the ALMS and at La Sarthe and would run at astronomical speeds if let loose on the banking at Daytona International Speedway and the consequences of something going wrong were only too easy to imagine. The open cars also had a potential safety issue, highlighted by the fatal accident of Jeff Clinton at Homestead early in the 2002 Grand-Am season. The flurry of legal action that followed that accident focused minds in Volusia County.

Cost was also a problem, even manufacturers of the size of Cadillac realised that they could not outspend Audi in the spiralling arms race that motor sport has always been. Detroit would not sanction such expenditure that had little return on investment and in the face of a declining financial situation that would eventually require a US Government bail out. There was very definitely a finite limit of what competitors could be expected to spend.

The only realistic solution to the issues of cost for Grand-Am was to write the rule book themselves giving them total control over all aspects of their series and not being dependant on outside parties building cars to others’ regulations and also not having manufacturers dominate proceedings.

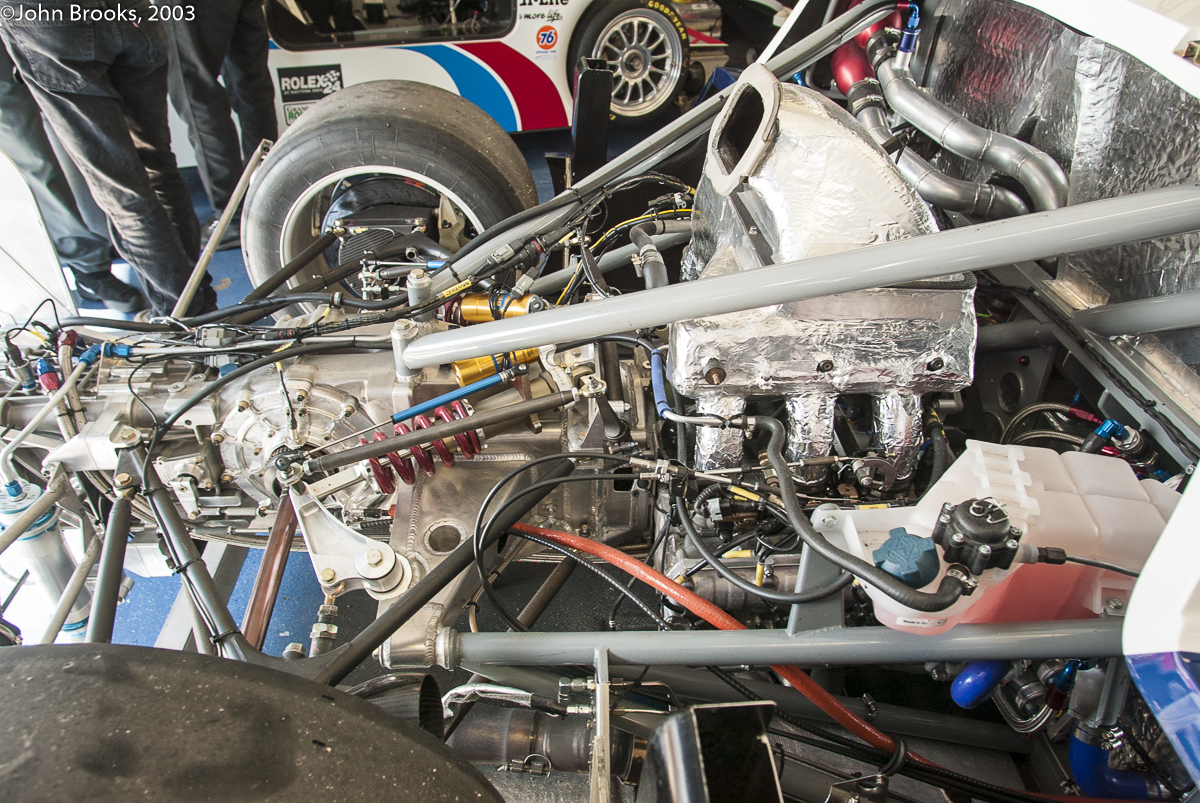

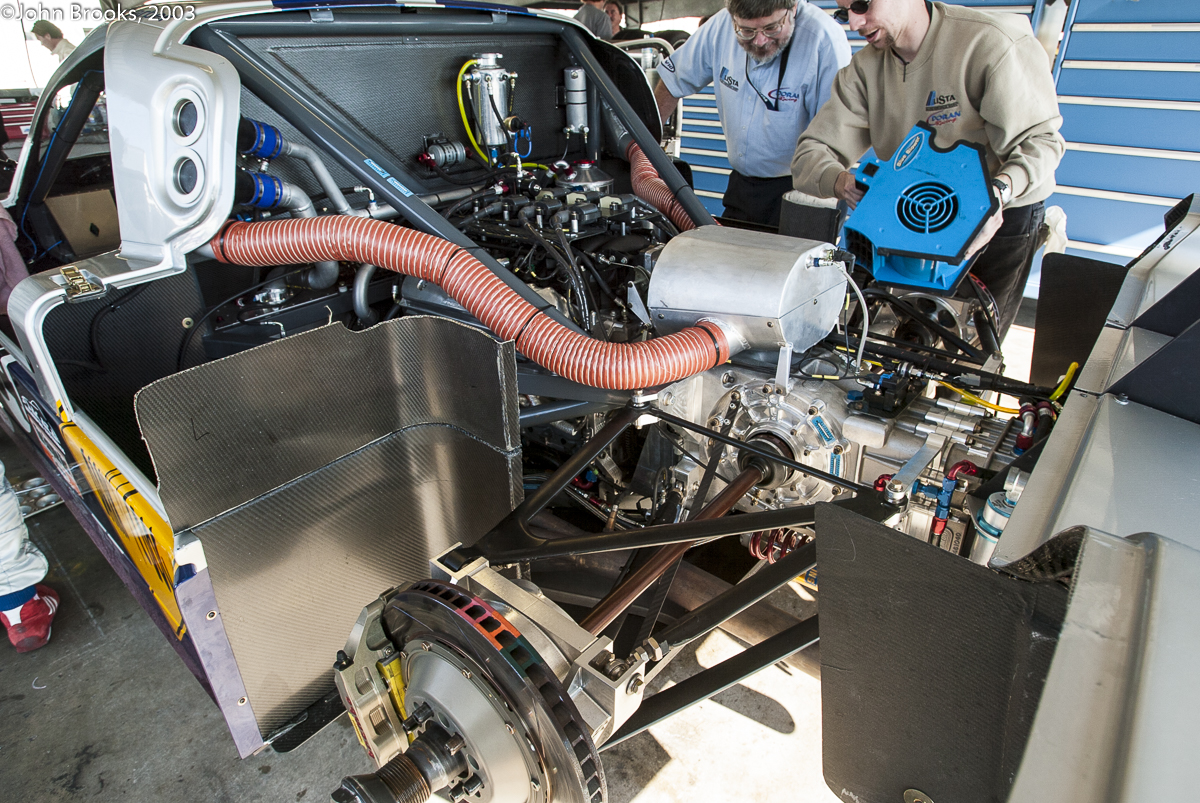

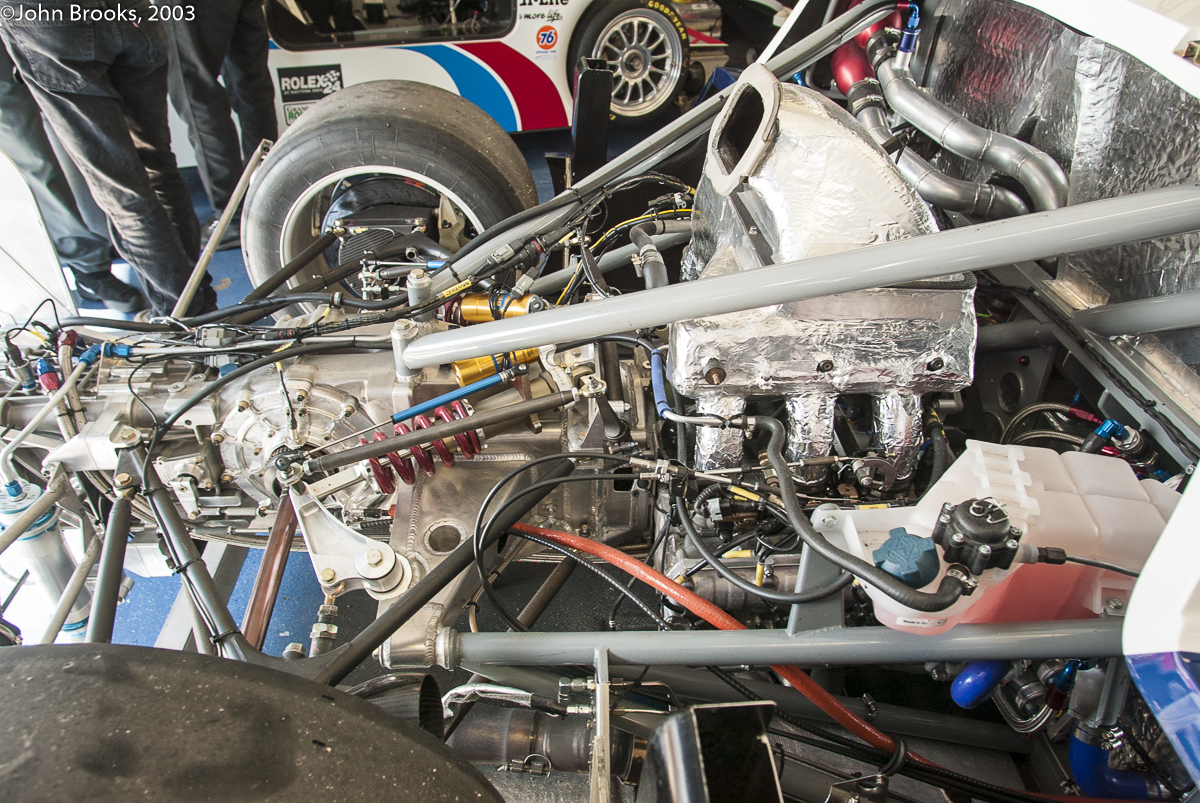

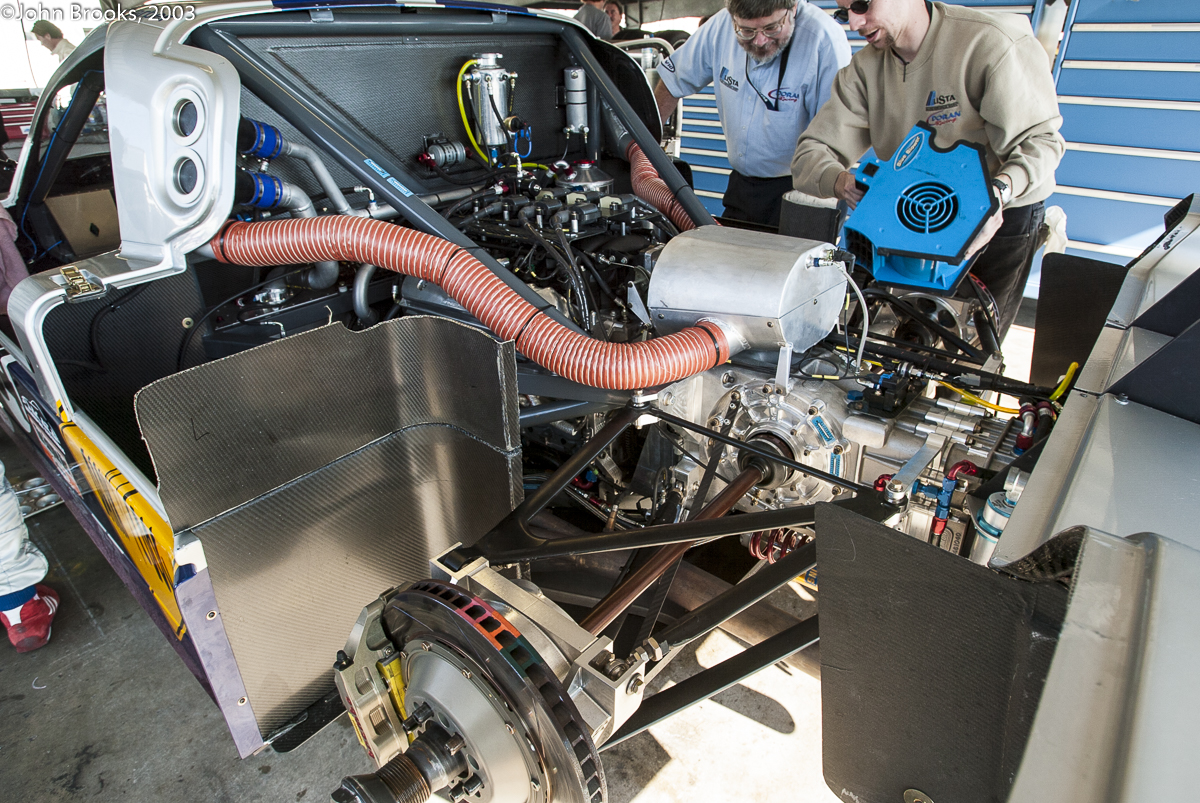

The high tech and costly solutions involving carbon fibre, Kevlar and electronic wizardry were out except on bodywork and ancillaries. The traditional tube-frame construction would the basis for all the cars. Seven different chassis were approved, along with engines that were also tightly regulated. Another benefit to Grand-Am was to lock in those teams that invested in Daytona Prototypes, there was nowhere else to race these odd machines.

Well that is how members of the media like myself and the fans that flock to DIS in late January first encountered the Daytona Prototypes in the flesh. They looked awful, especially compared with the Audis and Bentleys that would run at Sebring a few weeks later but they were affordable and a business could be made running them. In any case no one at Grand-Am was going to pay any attention to a bunch of whiny Europeans that only showed up once a year to enjoy some Floridian sunshine.

Mind you it was not just us Aliens that did not care for the first iteration of the DP. I have been in recent correspondence with one of the drivers who lined up at the sharp end of the grid on February 1st. His verdict was “Damn, that’s an ugly car!”

The half dozen Daytona Prototypes were stationed at the head of the 44 cars that started the Rolex 24 in 2003. Flags were at half-mast around the track as news came in that morning of the loss of the space shuttle Columbia over Texas as it headed for for its base at Cape Canaveral, it was a sobering moment.

The early laps were led by Maxwell in the Multimatic with the Brumos pair keeping a watchful eye.

Then the problems began as the Doran headed for the pits suffering with all manner of issues, it was too new to be racing at a place as tough as DIS. Retirement was the fate after 67 laps.

The Picchio ended up behind the wall with overheating issues that plagued it for the rest of the race.

Then the Multimatic suffered a broken throttle cable which was repaired but cost the team many laps that they struggled to make up, the days of a big speed differential of the prototypes over the GTs were over.

The Fabcars were leading as the sun set with the Toyota powered car following the Brumos entry.

Disaster struck the #58 as the normally bullet proof Porsche engine suffered a failure, perhaps the bit that was most expected to last. Two DPs out as the long dark night arrived.

More throttle problems for the Multimatic during the night ended their challenge for overall honors.

The best of the DPs was the #59 but a trip off track to avoid contact with a stationary, stranded GT caused all manner of issues that dogged the car for the rest of the race.

All of this misfortune handed the Rolex 24 to the Racer’s Group Porsche 911 GT3 RS, the hounds had outlasted the hare.

The best result for the Daytona Prototypes was a fine fourth overall for Multimatic, always playing catch up after their unplanned pit visits. The drivers had the consolation prize of new Rolex watches.

The Daytona Prototype era had got off to a shaky start but they would assert their authority over the GT classes in the future and by the Gen3 they looked like proper racing cars. They have provided the foundation for Grand-Am and now the IMSA championships. Few would have bet on that back in 2003 but they have earned their place in the history books.

John Brooks, September 2016