Our old friend János Wimpffen has agreed to share his wisdom with us here on DDC………this is the first of (hopefully) many despatches from the front.

This is the first of series of reports which in cyber-terminology may be labeled as a “blog”. Much like others blogs it will be cumulative effort, building up from the start. It will have the elements of a travelogue, with commentary on local customs as well as more traditional race reportage—albeit in a more summary form. The objective is not to provide a lap-by-lap or hour-by-hour accounting of an event. Other sites do that, ranging from merely adequate to exemplary. Rather, a key point is to convey the atmosphere of a race meeting, offering some grander perspective on proceedings. But such embellishment is not being submitted merely for dispassionate pleasure but rather to position each race within the rather broad tent that defines contemporary sports car racing.

To this end, we begin with what might be termed as a primer on the state of this branch of the motor racing discipline, circa 2015. The tone is to aim for a comfortable middle ground. Often, race reportage presumes that one is already familiar with the cadence of each series, conversant with the names of the teams and drivers, and aware of all the subtleties of rules and technical changes. We will not presume that, nor will we presume that the reader will necessarily be riding on every last nuance of detail. Instead, what we do postulate that since you, Dear Reader, are here—you are already a great fan of sports car racing, only that you are content to be familiar with the general trends. In such manner, there should be nuggets of enjoyment here, regardless of your ongoing level of interest and monitoring of each race and series.

Sports car racing, for many of its decades of history, has been subject to that old admonishment, “may you live in interesting times.” It is arguable as where exactly the 2015 season sits along the spectrum of interesting to dull, but clearly the tendency is towards the fascinating end.

The WEC has truly become global in scope and following, meeting or exceeding most expectations. The other series had at various times made forays into having a broader geographical reach but with the advent of the WEC they are all comfortably ensconced within a continental or regional framework.

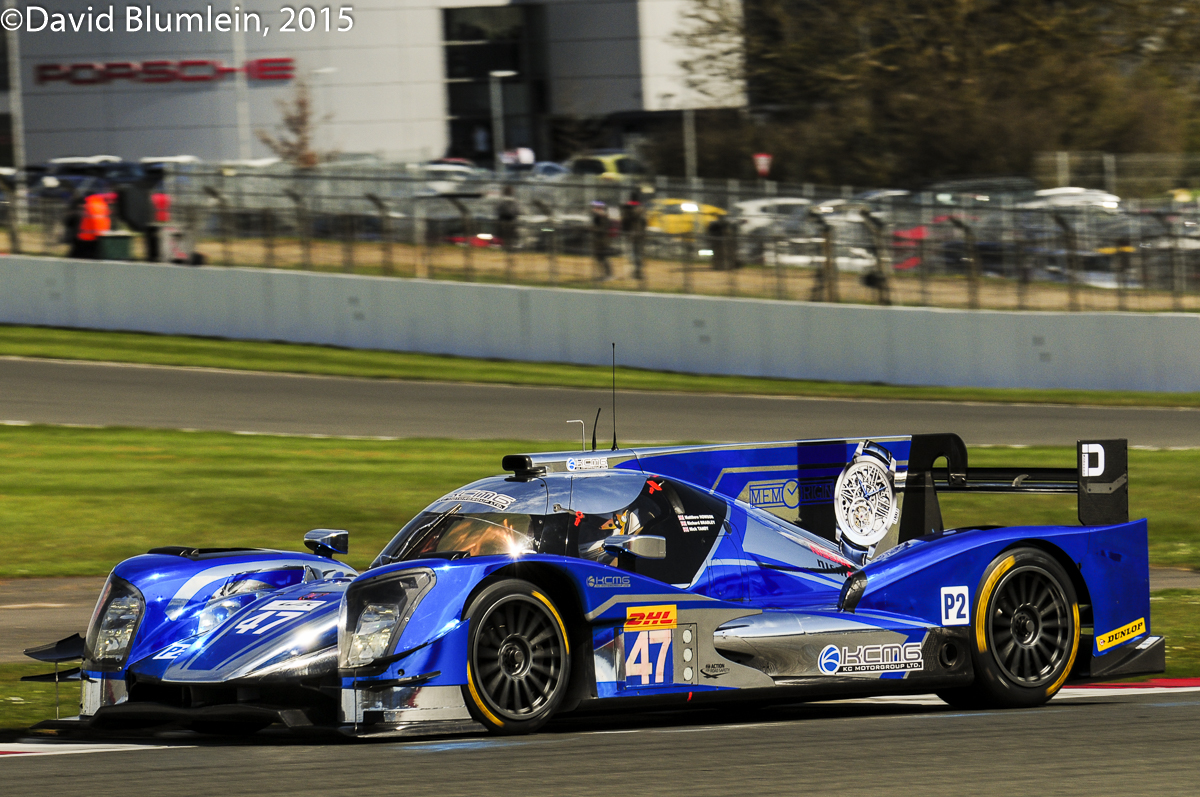

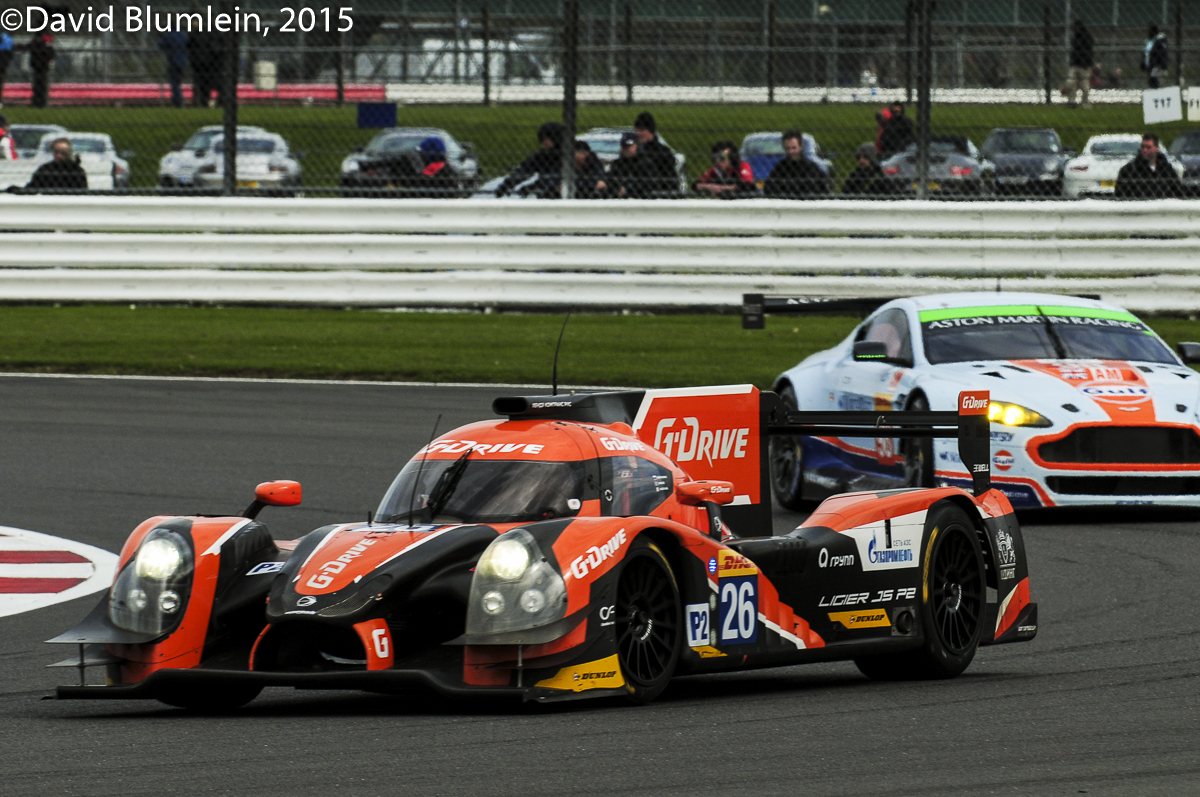

The most senior of these series and the most stable is the European Le Mans Series. Its origins were in the early noughties and ELMS has LM P2 as its headline class. The LM P2 category has come a long way over the course of a decade. It began purely as support to LM P1 and was always intended for privateer entrants. It still has that approach but LM P2 has matriculated from a “last man (barely) standing” into a consistent pattern of close, reliable racing at a very high level of professionalism. LM P2 shares a trait that many such classes have exhibited in the past. There was a time when the category was populated by a very colorful array of chassis and engine combinations. Over time a few key constructors have risen to the fore, in particularly Oreca, which dominates numerically as does the Nissan engine. Ligier and the Onroak-built Morgan, along with the BMW derived Judd motors have added variety and genuine heft to the class. They have been joined this year by the Gibson marque, which is actually the reincarnation of Zytek, the car itself a descendant of Reynard, by YGK and DBA (not at all confusing).

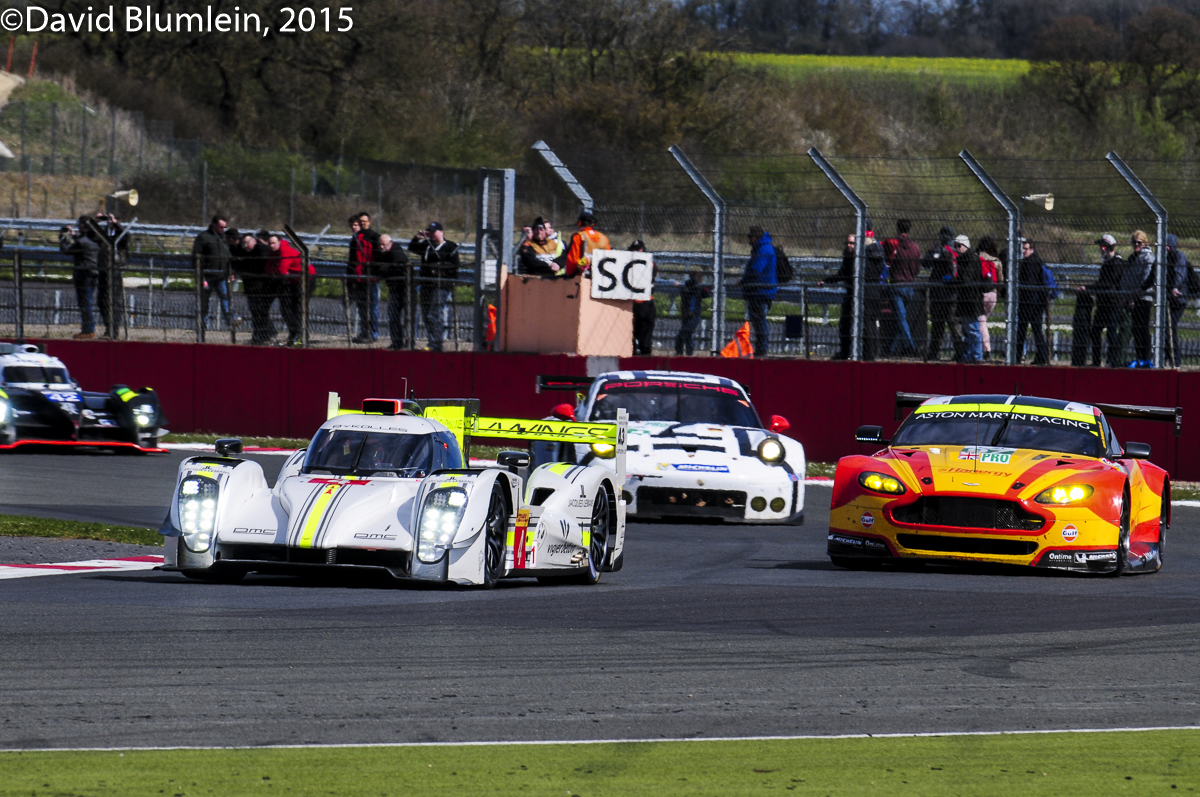

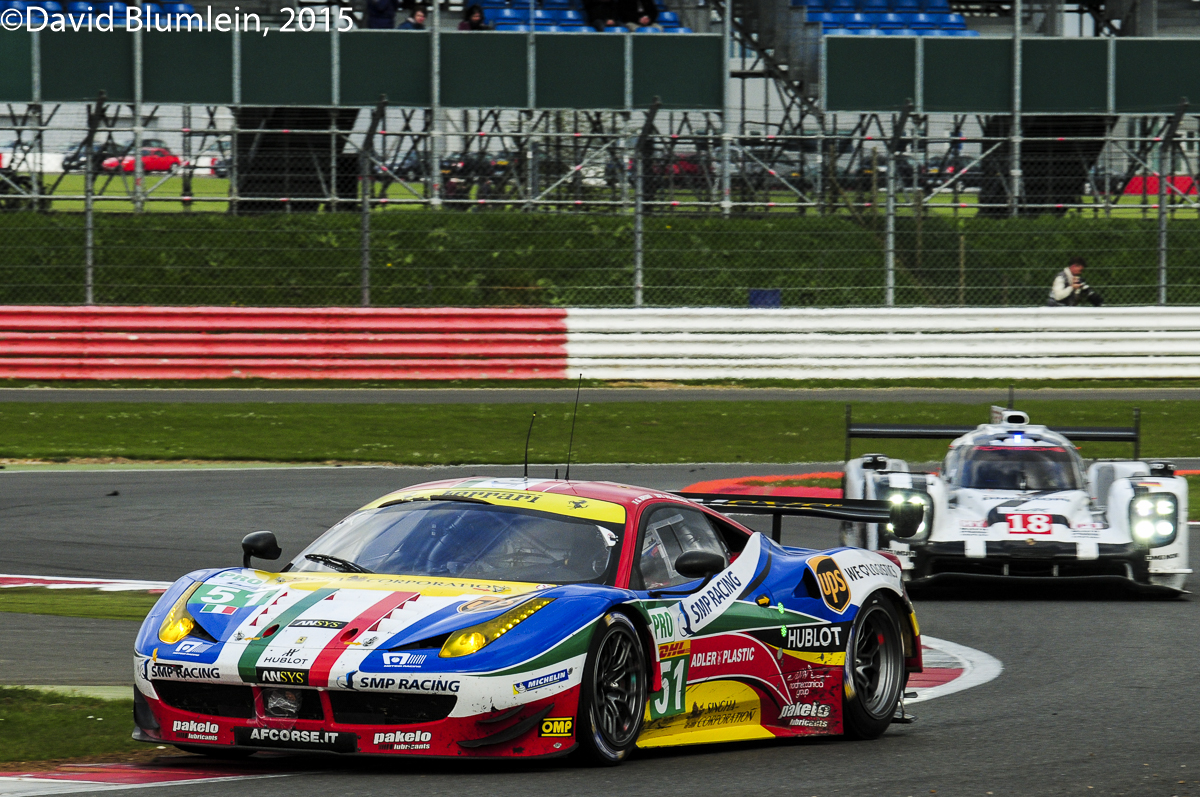

Three GT classes can be seen in the ELMS and as with all other series; Grand Touring is in rude health. For past decade or so there have been three developments that have cemented GT’s popularity and close racing. First and perhaps foremost has been the emergence of GT3. These cars follow fairly tight homologation standards, are designed to be user friendly—read, good for novice and gentleman drivers, and are subject to the often controversial Balance of Performance standards. BOP’s aim is to regulate that no model exerts undue advantage for too long. Purists may bemoan that BOP goes against the grain of motor sport as being a contest for improved technology, but few can argue with results showing some thrilling contests. Of course, those at the short end of a BOP adjustment will complain—but such wailing has been with us since well before board tracks. BOP is practiced across a variety of classes and series and is the second pillar of GT’s ascendancy. It is manifested on cars largely through playing with aerodynamic features, widening and narrowing inlet air restrictors, fuel capacity, and occasionally through using ballast weights.

The third major development over the past decade has been the introduction of driver classification systems. Depending upon experience, age, and history of success, drivers are rated as Platinum, Gold, Silver, or Bronze. Each series and each class then employs rules as to the mix required on the roster and for minimum/maximum times behind the wheel. Perhaps paradoxically after having noted the importance of GT3, it plays no role in the FIA WEC and is only one of the two GT classes in ELMS.

There is an altogether new “budget” class in the ELMS for 2015, LMP3. Chassis specifications are quite restricted with Ginetta being the first to build to the regulations. All cars use identical 5.0-liter Nissan engines. ELMS race are uniformly four hours in duration.

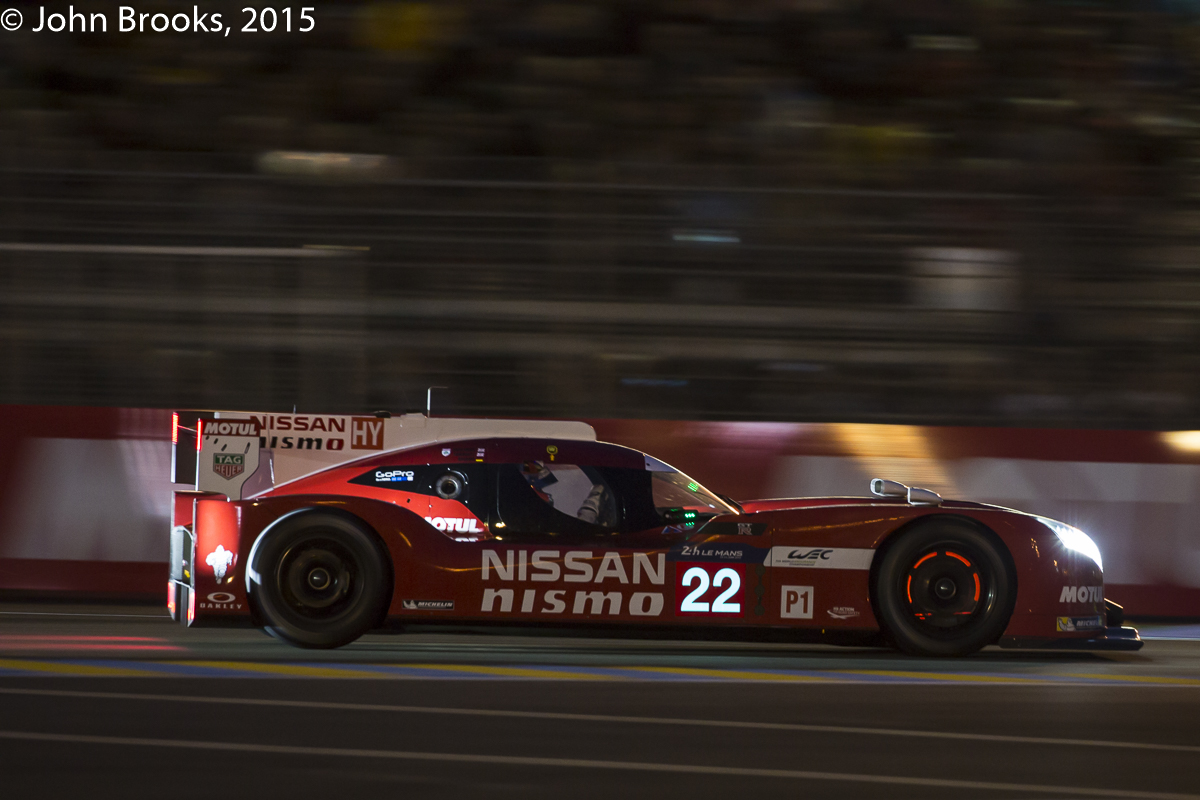

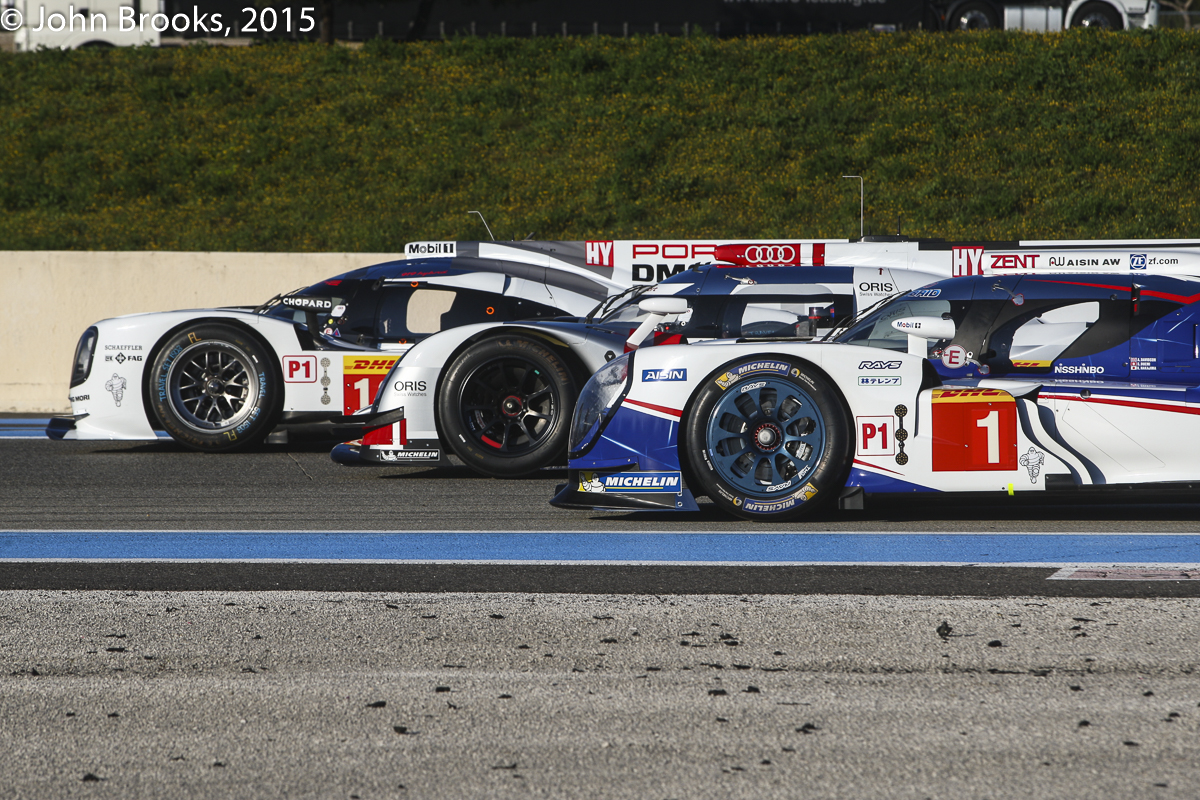

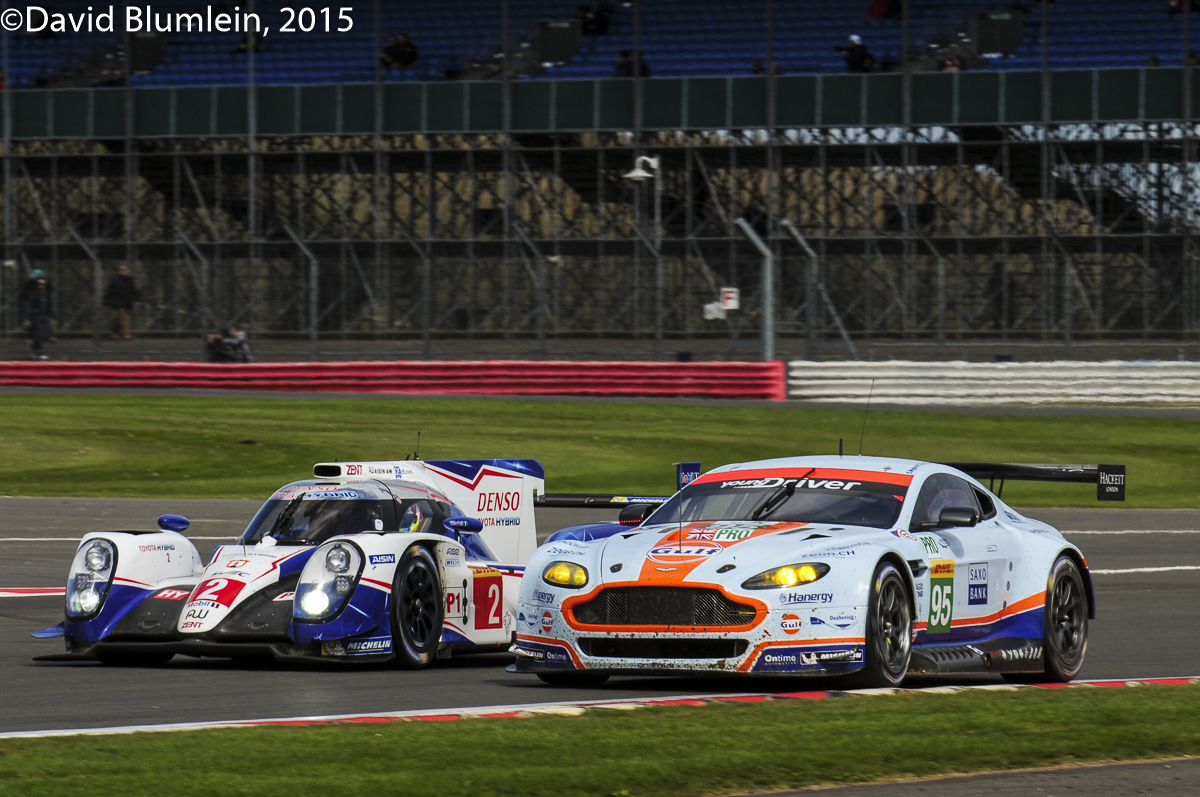

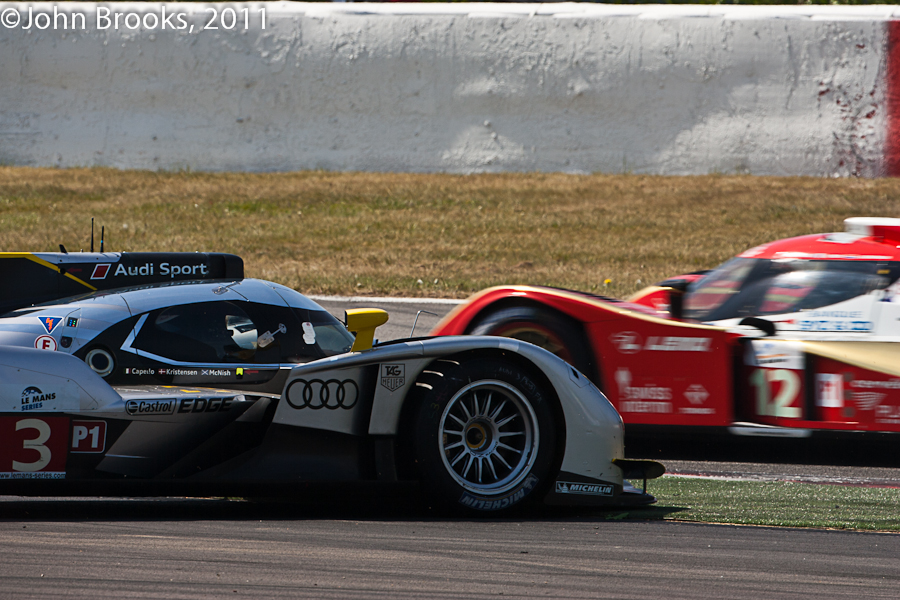

Most importantly, after 20 years in the wilderness, endurance racing has a World Championship, a platform for manufacturers to applying their technology and marketing. Now in its fourth season, the FIA World Endurance Championship is thriving. It has become the nexus of the most technologically advanced racing vehicles found anywhere. With three manufacturers (and a fourth if Nissan doesn’t fall flat) there is competition at the highest level in the hybrid based LM P1 class. The undercard of the LM P2 and GTE classes is as good as ever. Once again the Le Mans 24 Hours is part of the Championship—although the French classic has always more than adequately held up most of the sports car racing sky even when running to an independent formula. The FIA WEC hews to a very consistent schedule of locations and race lengths, with six hours being the norm apart from Le Mans. Classic European venues are matched further abroad by important new locales like the Circuit of the Americas in Texas, Shanghai, and Bahrain as well as the return of the venerable Fuji.

While it is vital to introduce and position the FIA WEC at the pinnacle of sports car racing there were no races attended during these particular outings. One of the attributes that sets the current era apart from the last time that there was a bona fide world championship (1992 and before) was that back then it was pretty much the only game in town. Yes, IMSA GTP was quite significant during the 1980s, albeit only in North America, but there wasn’t the plethora of other major events as there is now. This is partly the legacy of the lack of a world series during the intervening period. It allowed such players as IMSA, Grand-Am, SRO, ELMS, and (on a more fractured basis) some Asian series to cycle through, have their own apogees and perigees, and leave a lasting influence on sports car racing in general.

János Wimpffen, July 2015